Fine tune large protein model (ProtTrans) using HuggingFace

| Author(s) |

|

| Reviewers |

|

OverviewQuestions:

Objectives:

How to load large protein AI models?

How to fine-tune such models on downstream tasks such as post-translational site prediction?

Requirements:

Learn to load and use large protein models from HuggingFace

Learn to fine-tune them on specific tasks such as predicting dephosphorylation sites

- tutorial Hands-on: JupyterLab in Galaxy

- tutorial Hands-on: A Docker-based interactive Jupyterlab powered by GPU for artificial intelligence in Galaxy

Time estimation: 1 hourSupporting Materials:Published: Jun 17, 2024Last modification: Apr 8, 2025License: Tutorial Content is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The GTN Framework is licensed under MITpurl PURL: https://gxy.io/GTN:T00442rating Rating: 4.5 (0 recent ratings, 2 all time)version Revision: 4

The advent of large language models has transformed the field of natural language processing, enabling machines to comprehend and generate human-like language with unprecedented accuracy. Pre-trained language models, such as BERT, RoBERTa, and their variants, have achieved state-of-the-art results on various tasks, from sentiment analysis and question answering to language translation and text classification. Moreover, the emergence of transformer-based models, such as Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) and its variants, has enabled the creation of highly advanced language models to generate coherent and context-specific text. The latest iteration of these models, ChatGPT, has taken the concept of conversational AI to new heights, allowing users to engage in natural-sounding conversations with machines. However, despite their impressive capabilities, these models are imperfect, and their performance can be significantly improved through fine-tuning. Fine-tuning involves adapting the pre-trained model to a specific task or domain by adjusting its parameters to optimise its performance on a target dataset. This process allows the model to learn task-specific features and relationships that may not be captured by the pre-trained model alone, resulting in highly accurate and specialised language models that can be applied to a wide range of applications. In this tutorial, we will discuss and fine-tune large language model trained on protein sequences ProtT5, exploring the benefits and challenges of this approach, as well as the various techniques and strategies such as low ranking adaptations (LoRA) that can be employed to fit large language models with billions of parameters on regular GPUs. Protein large language models (LLMs) represent a significant advancement in Bioinformatics, leveraging the power of deep learning to understand and predict the behaviour of proteins at an unprecedented scale. These models, exemplified by the ProtTrans suite, are inspired by natural language processing (NLP) techniques, applying similar methodologies to biological sequences. ProtTrans models, including BERT and T5 adaptations, are trained on vast datasets of protein sequences from databases such as UniProt and BFD, storing millions of protein sequences and enabling them to capture the complex patterns and functions encoded within amino acid sequences. By interpreting these sequences much like languages, protein LLMs offer transformative potential in drug discovery, disease understanding, and synthetic biology, bridging the gap between computational predictions and experimental biology. In this tutorial, we will fine-tune the ProtT5 pre-trained model for dephosphorylation site prediction, a binary classification task.

AgendaIn this tutorial, we will cover:

Fine tuning to predict dephosphorylation sites

Fine-tuning is a transfer learning method where a pre-trained model (e.g. LLM) is further trained on a new, usually smaller dataset to adapt it to a specific task. This process begins with a model trained on a large, general dataset. By leveraging the knowledge already captured in the pre-trained model’s weights, fine-tuning allows for more targeted and efficient learning on the new dataset, requiring fewer computational resources and less training time than training a model from scratch. The fine-tuning process typically involves adjusting several hyperparameters, such as learning rate, as the pre-trained model’s parameters are updated to fit the new data better. The method is particularly effective in scenarios where the new dataset is too small to train a robust model independently, as it benefits from the general patterns and features learned during the initial (pre) training phase. Fine-tuning keeps a balance between retaining the model’s original capabilities and adapting to the specific nuances of the new task, leading to improved performance in a wide range of applications, from natural language processing to computer vision. The protT5 model used in this tutorial has been trained on UniRef50 protein database consisting of 45 million protein sequences. The model captures general features from the large training sequences and is available for further training tasks such as fine-tuning on HuggingFace.

Dephosphorylation

Dephosphorylation is a biochemical process (post-translational modification) involving removing a phosphate group from an organic compound, typically mediated by phosphatase enzymes. This process regulates cellular functions, including signal transduction, metabolism, and protein activity. By removing phosphate groups from proteins, phosphatases counterbalance the actions of kinases, which add phosphate groups, thus maintaining the dynamic equilibrium of phosphorylation states within the cell. Dephosphorylation can activate or deactivate enzymes and receptors, alter protein-protein interactions, and influence the cellular localisation of proteins. This regulation is essential for many physiological processes, such as cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis. Disruptions in dephosphorylation mechanisms are associated with numerous diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disorders, highlighting the importance of precise control over this process for maintaining cellular health and function. Labelled datasets specifying whether a protein sequence contains dephosphorylation sites are scarce. Chaudhari et al. has used deep learning techniques to classify dephosphorylation sites but on a small dataset consisting of around 1,000 protein sequences having dephosphorylation sites at Serine (S), Threonine (T) and Tyrosine (Y). We explore fine-tuning a pre-trained ProtT5 model on a dephosphorylation dataset to showcase an approach for classifying protein sequences. In the tutorial, only those sequences having Y site as dephosphorylated are used for fine-tuning to restrict the training time to a reasonable limit. In the following sections, the GPU-enabled JupyterLab tool in Galaxy is used to fine-tune the ProtT5 model to learn and predict dephosphorylation sites.

JupyterLab in Galaxy Europe

Open JupyterLab

Hands On: GPU-enabled Interactive Jupyter Notebook for Machine Learning

- GPU-enabled Interactive Jupyter Notebook for Machine Learning

- “Do you already have a notebook?”:

Start with a code repository- “Online code repository (Git-based) URL”:

https://github.com/anuprulez/fine-tune-protTrans-repository- Click “Run Tool”

CommentThe above step automatically fetches the notebook and datasets from the provided GitHub URL and initiates a JupyterLab. If you do not have access to this resource in Galaxy Europe, please apply for it at: Access GPU-JupyterLab. It may take a day or two to receive access.

Fine-tuning notebook

From the cloned repository, open the fine-tune-protTrans-dephophorylation.ipynb notebook. The notebook contains all the necessary scripts for processing protein sequences, creating and configuring protein large language models, training it on the protein sequences evaluating them on the test protein sequences and visualising results. Let’s look at these key steps of fine-tuning.

Install necessary Python packages

The protein large language model has been developed using Pytorch and the model weights are stored at HuggingFace. Therefore, packages such as Pytorch, Transformers, and SentencePiece must be installed in the notebook to recreate the model. Additional packages such as Scikit-learn, Pandas, Matplotlib and Seaborn are also required for data preprocessing, manipulation and visualisation of model training and test performances. All the necessary packages are installed in the notebook using !pip install command. Note: the installed packages have a lifespan equal to the notebook sessions. When a new session of JupyterLab is created, all the packages need to be installed again.

Fetch and split data

After installing and importing all the necessary packages, protein sequences (available as a FASTA file) and their labels are read into the notebook. These sequences are further divided into training and validation sets. The training set is used for fine-tuning the protein large language model, and the validation set is used for model evaluation after each training epoch.

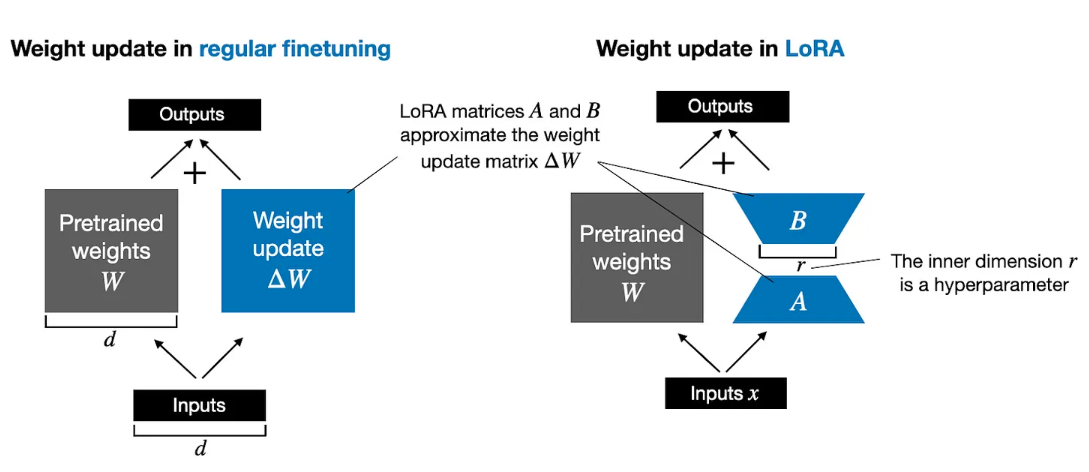

Define configurations for LoRA with transformer (ProtT5) model

The protein large language model (ProtT5) used in this tutorial has over 1.2 billion parameters (1,209,193,474). Training such a large model on any commercial GPU with 15GB of memory is impossible. LoRA, the low-ranking adaption technique, has been devised to make the fine-tuning process feasible on such GPUs. LoRA learns low-rank matrices and, when multiplied, takes the shape of a matrix of the original large language model. During fine-tuning, the weight matrices of the original large language model are kept frozen (not updated) while only these low-rank matrices are updated. Once fine-tuning is finished, these low-rank matrices are combined with the original frozen weight matrices to update the model. The low-rank matrices contain all the knowledge obtained by fine-tuning a small dataset. This approach helps retain the original knowledge of the model while adding the additional knowledge from the fine-tuning dataset. When LoRA is applied to the ProtT5 model, the trainable parameters become a little over 3 million (3,559,426), making it possible to fine-tune on a commercial GPU with at least around 10 GB of memory. The following figure compares fine-tuning with and without LoRA. Fine-tuning without LoRA requires additional weight matrices to be the same size as the original model, which needs much more computational resources than LoRA, where much smaller weight matrices are learned.

Open image in new tab

Open image in new tabCreate ProtT5 model

The ProtT5 model (inspired by T5) has two significant components - encoder and sequence classifier. Encoder learns a representation of protein sequences, and classifier is used for downstream classification of the learned representations of sequences. The self-attention technique is used to learn sequence representations by computing weights of highly interacting regions in sequences, thereby establishing long-range dependencies. Amino acids in protein sequences are represented in vector spaces in combination with positional embedding to maintain the order of amino acids in sequences.

Create a model training method and train

Once the model architecture is created, the weights of the pre-trained ProtT5 are downloaded from HuggingFace. HuggingFace provides an openly available repository of pre-trained weights of many LLM-like architectures such as ProtT5, Llama, BioGPT and so on. The download of the pre-trained weights is facilitated by a Python package, Transformers, which provides methods for downloading weight matrices and tokenisers. After downloading the model weights and tokeniser, the original model is modified by adding LoRA layers to have low-rank matrices and the original weights are frozen. This brings down the number of parameters of the original ProtT5 model from 1.2 billion to 3.5 million. Then, the LoRA updated model is trained for several epochs until the error rate stops decreasing which signifies training stabilisation. Next, the fine-tuned model is saved to a file where it can be reused for prediction.

Analyse results

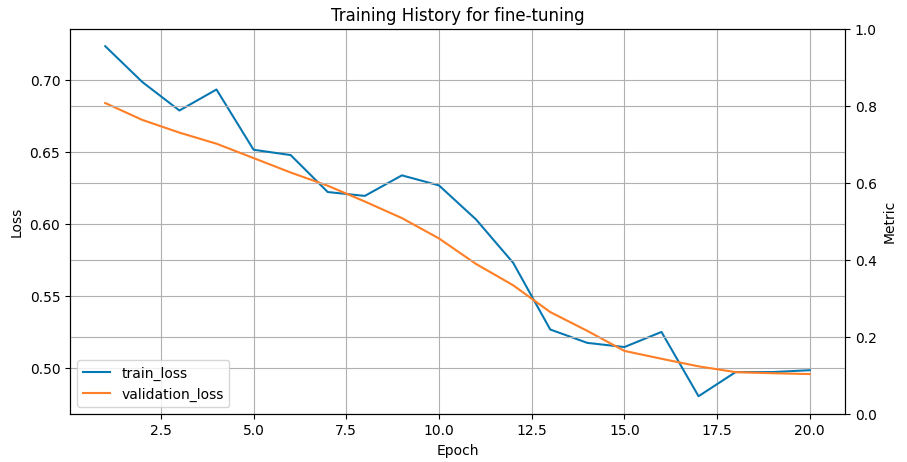

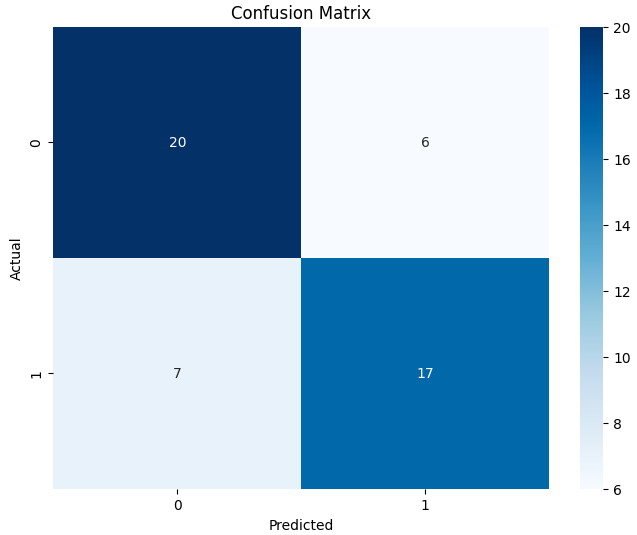

The saved trained model is recreated and used to predict the classes of protein sequences from the test set. Different metrics assess fine-tuning performance, such as Matthews’s correlation coefficient (MCC), specificity, sensitivity, accuracy, ROC-AUC and confusion matrix. The higher the value of MCC and closer to 1, the better the correlation between true and predicted classes. High specificity means few false positive results in the predictions, while high sensitivity refers to a few false negatives. Accuracy provides the fraction of correctly predicted sequences from the entire test set. The ROC-AUC metric specifies how well a classifier distinguishes between two classes in a binary classification problem. Its value varies between 0 and 1, where 1 means the perfect classifier and 0.5 means random guessing. The training history plot below shows the error of the fine-tuning process going down and stabilising around training iteration 20.

Open image in new tab

Open image in new tabThe performance of the fine-tuned model is reasonable, showing ROC-AUC as 0.8 and an accuracy of 0.74, classifying 37 out of 50 sequences correctly. The confusion matrix further elaborates on the fine-tuning results, showing the classification performance of both classes (0 and 1).

Open image in new tab

Open image in new tabConclusion

In the tutorial, we have discussed an approach to fine-tune a large language model trained on millions of protein sequences to classify dephosphorylation sites. Using low-ranking adaptation technique, it becomes possible to fine-tune a model having 1.2 billion trainable parameters by reducing it to contain just 3.5 million ones. The availability of the fine-tuning notebook provided with the tutorial and the GPU-JupyterLab infrastructure in Galaxy simplify the complex process of fine-tuning on different datasets. In addition to classification, it is also possible to extract embeddings/representations of entire protein sequences and individual amino acids in protein sequences.