Foundational Aspects of Machine Learning using Python

| Author(s) |

|

| Editor(s) |

|

| Reviewers |

|

OverviewQuestions:

Objectives:

How can we use Machine-Learning to make more generalizable models?

What are the key components of a supervised learning problem, and how do they influence model performance?

How do classification and regression tasks differ in supervised learning, and what types of models are suitable for each?

What strategies can we employ to ensure our Machine Learning models generalize well to unseen data?

How can we use Machine Learning to make more generalizable models that perform well on diverse datasets?

What are some practical steps for applying Machine Learning to real-world datasets, such as the transcriptomics dataset for predicting potato coloration?

Requirements:

Understand and apply the general syntax and functions of the scikit-learn library to implement basic Machine Learning models in Python.

Identify and explain the concepts of overfitting and underfitting in Machine Learning models, and discuss their implications on model performance.

Analyze the need for regularization techniques and justify their importance in preventing overfitting and improving model generalization.

Evaluate the effectiveness of cross-validation and test sets in assessing model performance and implement these techniques using scikit-learn.

Compare different evaluation metrics and select appropriate metrics for imbalanced datasets, ensuring accurate and meaningful model assessment.

- tutorial Hands-on: Introduction to Python

- tutorial Hands-on: Python - Warm-up for statistics and machine learning

Time estimation: 3 hoursLevel: Intermediate IntermediateSupporting Materials:Published: Mar 11, 2025Last modification: May 19, 2025License: Tutorial Content is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The GTN Framework is licensed under MITpurl PURL: https://gxy.io/GTN:T00524version Revision: 3

Best viewed in a Jupyter NotebookThis tutorial is best viewed in a Jupyter notebook! You can load this notebook one of the following ways

Run on the GTN with JupyterLite (in-browser computations)

Launching the notebook in Jupyter in Galaxy

- Instructions to Launch JupyterLab

- Open a Terminal in JupyterLab with File -> New -> Terminal

- Run

wget https://training.galaxyproject.org/training-material/topics/statistics/tutorials/intro-to-ml-with-python/statistics-intro-to-ml-with-python.ipynb- Select the notebook that appears in the list of files on the left.

Downloading the notebook

- Right click one of these links: Jupyter Notebook (With Solutions), Jupyter Notebook (Without Solutions)

- Save Link As..

Machine Learning is a subset of artificial intelligence that involves training algorithms to learn patterns from data and make predictions or decisions without being explicitly programmed. It has revolutionized various fields, from healthcare and finance to autonomous vehicles and natural language processing.

This tutorial is designed to equip you with essential knowledge and skills in Machine Learning, setting a strong foundation for exploring advanced topics such as Deep Learning.

The objective of this tutorial is to introduce you to some foundational aspects of Machine Learning which are key to delve in other topics such as Deep Learning. Our focus will be on high-level strategies and decision-making processes related to data and objectives, rather than delving into the intricacies of specific algorithms and models. This approach will help you understand the broader context and applications of Machine Learning.

We will concentrate on supervised learning, where the goal is to predict a “target” variable based on input data. In supervised learning, the target variable can be:

- Categorical: In this case, we are performing classification, where the objective is to assign input data to predefined categories or classes.

- Continuous: Here, we are conducting regression, aiming to predict a continuous value based on the input data.

While classification and regression employ different models and evaluation metrics, many of the underlying strategies and principles are shared across both types of tasks.

In this tutorial, we will explore a practical example using a transcriptomics dataset to predict phenotypic traits in potatoes, specifically focusing on potato coloration. The dataset has been pre-selected and normalized to include the 200 most promising genes out of approximately 15,000, as proposed by Acharjee et al. 2016. This real-world application will help you understand how to apply Machine Learning techniques to solve practical problems.

AgendaIn this tutorial, we will cover:

Prepare resources

Let’s start by preparing the environment

Install dependencies

The first step is to install the required dependencies if they are not already installed:

!pip install matplotlib

!pip install numpy

!pip install pandas

!pip install seaborn

!pip install scikit-learn

Import tools

Let’s now import them.

import matplotlib.pylab as pylab

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

Configure for plotting

For plotting, we will use Matplotlib, a popular plotting library in Python. We would like to customize the appearance of plots to enhance readability and ensure that all plots generated during the tutorial will have a consistent and professional appearance, making them easier to read and interpret:

pylab.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = 5, 5

plt.rc("font", size=10)

plt.rc("xtick", color="k", labelsize="medium", direction="in")

plt.rc("xtick.major", size=8, pad=12)

plt.rc("xtick.minor", size=8, pad=12)

plt.rc("ytick", color="k", labelsize="medium", direction="in")

plt.rc("ytick.major", size=8, pad=12)

plt.rc("ytick.minor", size=8, pad=12)

QuestionWhat are the above commands doing?

pylab.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = 5, 5: Sets the default figure size to 5x5 inches. This ensures that all plots generated will have a consistent size unless otherwise specified.plt.rc("font", size=10): Sets the default font size for all text elements in the plots to 10. This includes titles, labels, and tick marks.plt.rc("xtick", color="k", labelsize="medium", direction="in"): Configures the x-axis ticks:

color="k": Sets the tick color to black.labelsize="medium": Sets the label size to medium.direction="in": Sets the direction of the ticks to point inward.plt.rc("xtick.major", size=8, pad=12): Configures the major x-axis ticks:

size=8: Sets the length of the major ticks to 8 points.pad=12: Sets the padding between the tick labels and the plot to 12 points.- *

plt.rc("xtick.minor", size=8, pad=12): Configures the minor x-axis ticks with the same settings as the major ticks:

size=8: Sets the length of the minor ticks to 8 points.pad=12: Sets the padding between the tick labels and the plot to 12 points.plt.rc("ytick", color="k", labelsize="medium", direction="in"): Configures the y-axis ticks with the same settings as the x-axis ticks:

color="k": Sets the tick color to black.labelsize="medium": Sets the label size to medium.direction="in": Sets the direction of the ticks to point inward.plt.rc("ytick.major", size=8, pad=12): Configures the major y-axis ticks:

size=8: Sets the length of the major ticks to 8 points.pad=12: Sets the padding between the tick labels and the plot to 12 points.plt.rc("ytick.minor", size=8, pad=12): Configures the minor y-axis ticks with the same settings as the major ticks:

size=8: Sets the length of the minor ticks to 8 points.pad=12: Sets the padding between the tick labels and the plot to 12 points.

Get data

Let’s now get the data. As mentioned in the introduction, we will use data from Acharjee et al. 2016 where they used transcriptomics dataset to predict potato coloration. The dataset has been pre-selected and normalized to include the 200 most promising genes out of approximately 15,000.

First, let’s import the metadata of the studied potatoes:

file_metadata = "https://github.com/sib-swiss/statistics-and-machine-learning-training/raw/refs/heads/main/data/potato_data.phenotypic.csv"

df = pd.read_csv(file_metadata, index_col=0)

Question

- How many potatoes and metadata do we have?

- In which column is the color information?

Let’s get the dimension of the dataframe:

df.shapeThe dimension of the dataframe is 86 rows and 8 columns. So there are 86 potatoes and 8 metadata for each.

Flesh Colourcolumn

For the sake of our story, we will imagine that out of the 86 potatoes in the data, we have only 73 at the time of our experiment. We put aside the rest for later.

i1 = df.index[:73]

i2 = df.index[73:]

We are interested in the colors of the potatoes, stored in the Flesh Colour column:

y = df.loc[i1, "Flesh Colour"]

Questiony.describe()count 73.000000 mean 24.473845 std 12.437785 min 6.992000 25% 13.484500 50% 24.746500 75% 30.996200 max 57.035100 Name: Flesh Colour, dtype: float64

- How many entries are non-null?

- What is the average value of the dataset?

- What is the standard deviation?

- What is the minimum value?

- What is the first quartile (25th percentile)?

- What is the median (50th percentile)?

- What is the third quartile (75th percentile)?

- What is the maximum value?

- 73

- mean = 24.47

- std = 12.44

- min = 6.992000

- 25% = 13.484500

- 50% = 24.746500

- 75% = 30.996200

- max = 57.035100

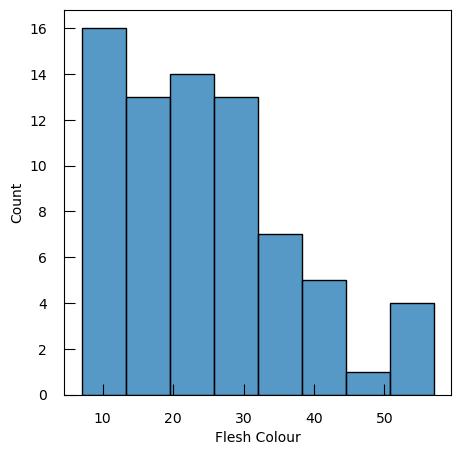

Let’s look at the distribution of the values:

sns.histplot(y)

We can now import transcriptomic data for the 200 selected genes in the 86 potatoes:

file_data = "https://github.com/sib-swiss/statistics-and-machine-learning-training/raw/refs/heads/main/data/potato_data.transcriptomic.top200norm.csv"

dfTT = pd.read_csv(file_data, index_col=0)

We keep only the 73 potatoes:

X = dfTT.loc[i1, :]

QuestionHow does the transcriptomic data look like?

X.head()

Genotype 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 … 190 191 192 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 CE017 0.086271 -0.790631 -0.445972 0.788895 0.510650 0.626438 0.829346 0.432200 -1.344748 1.794652 … -0.754008 -0.013125 0.852473 1.067286 0.877670 0.537247 1.251427 1.052070 -0.135479 -0.526788 CE069 -0.540687 0.169014 0.282120 -1.107200 -1.200370 0.518986 1.027663 -0.374142 -0.937715 1.488139 … -0.237367 0.684905 1.460319 -1.570253 0.547969 0.635307 0.257955 1.043724 0.733218 -1.768250 CE072 -1.713273 -1.400956 -1.543058 -0.930367 -1.058800 -0.455020 -1.302403 -0.110293 -0.332380 -0.232460 … -0.131733 -0.070336 0.821996 -1.566652 0.914053 -1.707726 0.498226 -1.500588 0.361168 -1.020456 CE084 -0.096239 -0.599251 -1.499636 -0.847275 -1.171365 -0.952574 -1.347691 0.561542 -0.335009 -0.702851 … -0.729461 0.135614 1.074398 0.629679 -0.691100 -1.247779 0.167965 -1.525064 0.150271 0.105746 CE110 -0.712374 -1.081618 -1.530316 -1.259747 -1.109999 -0.582357 -1.233085 0.008014 -0.915632 -0.746339 … -0.054882 0.363344 0.720155 0.465315 1.450199 -1.706606 0.602451 -1.507727 -2.207455 -0.139036 It is a tabular file with 73 rows and 201 columns. For each gene (column) and potatoes (row), we get the expression value of the gene

Linear regression

Linear regression is one of the most fundamental and widely used techniques in supervised Machine Learning. It is employed to model the relationship between a dependent variable (target) and one or more independent variables (features). The primary goal of linear regression is to fit a linear equation to observed data, enabling predictions and insights into the relationships between variables.

Approach 1: Simple linear regression

Let’s start by fitting a simple linear model with our gene expression values, and see what happens.

We start by importing elements from sklearn, a widely used library for Machine Learning in Python:

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

With

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression, we import theLinearRegressionclass from thelinear_model moduleofscikit-learn.LinearRegressionis used to create and train a linear regression model. It fits a linear equation to the observed data, allowing you to make predictions based on the relationship between the independent variables (features) and the dependent variable (target).

We now:

- Create an instance of the

LinearRegressionclass that will be used to fit the linear regression model to our data - Train the linear regression model using the training data:

X: the input feature matrix, where each row represents a sample and each column represents a feature, here a gene and its expressiony: the target vector, containing the values you want to predict, i.e. the flest color

- Use the trained linear regression model to make predictions on the same input data

X

lin_reg = LinearRegression()

lin_reg.fit(X, y)

y_pred = lin_reg.predict(X)

The next step is to evaluate the prediction using two evaluation metrics from the metrics module of scikit-learn:

r2_score: This function calculates the R-squared (coefficient of determination) score, which indicates how well the independent variables explain the variance in the dependent variable. An R-squared value of 1 indicates a perfect fit, while a value of 0 indicates that the model does not explain any of the variance.mean_squared_error: This function calculates the mean squared error (MSE), which measures the average of the squares of the errors—that is, the average squared difference between the observed actual outcomes and the outcomes predicted by the model. Lower values of MSE indicate better model performance.

from sklearn.metrics import r2_score, mean_squared_error

print(f"R-squared score: { r2_score(y ,y_pred ) :.2f}")

print(f"mean squared error: { mean_squared_error(y ,y_pred ) :.2f}")

Question

- What is the value of the R-squared score?

- What is the value of the mean squared error?

R-squared score: 1.00mean squared error: 0.00

Wow!! this is a perfect fit. But if you know anything about biology, or data analysis, then you likely suspect something wrong is happening.

The main library we will be using for machine learning is scikit-learn.

It should go without saying that if you have any questions regarding its usage and capabilities, your first stop should be their website,especially since it provides plenty of examples, guides, and tutorials.

Nevertheless, we introduce here the most common behavior of

sklearnobject.Indeed,

sklearnimplement machine learning algorithms (random forest, clustering algorithm,…), as well as all kinds of preprocessers (scalin, missing value imputation,…) with a fairly consistent interface.Most methods must first be instanciated as an object from a specific class:

## import the class, here RandomForestClassifier from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier ## instanciate the class object: my_clf = RandomForestClassifier()As it stands, the object is just a “naive” version of the algorithm.

The next step is then to feed the object data, so it can learn from it. This is done with the

.fitmethod:my_clf.fit( X , y )CommentIn this context,

Xis the data andyis the objective to attain. When the object is not an ML algorithm but a preprocessor, you only give theXNow that the object has been trained with your data, you can use it. For instance, to:

.transformyour data (typically in the case of a preprocessor):X_scaled = myScaler.transform(X) # apply a transformation to the data

.predictsome output from data (typically in the case of an ML algorithm, like a classifier)y_predicted = clf.predict(X) # predict classes of the training dataLast but not least, it is common in example code to “fit and transform” a preprocesser in the same line using ` .fit_transform`

X_scaled = myNaiveScaler.fit_transform(X) # equivalent to myNaiveScaler.fit(X).transform(X)That’s the basics. You will be able to experiment at length with this and go well beyond it.

Back to our potato model. At the moment, our claim is that our model can predict flesh color perfectly (RMSE=0.0) from the normalized expression of these 200 genes. But, say we now have some colleagues who come to us with some new potato data (the leftover data points)

Xnew = dfTT.loc[i2, :]

ynew = df.loc[i2, "Flesh Colour"]

We apply the model on the new data

ynew_pred = lin_reg.predict(Xnew)

QuestionHow is the prediction in term of R-squared score and mean squared error?

print(f"new data R-squared score: { r2_score( ynew , ynew_pred ) :.2f}") print(f"new data mean squared error: { mean_squared_error( ynew , ynew_pred ) :.2f}")new data R-squared score: 0.47 new data mean squared error: 130.47The values are not really good.

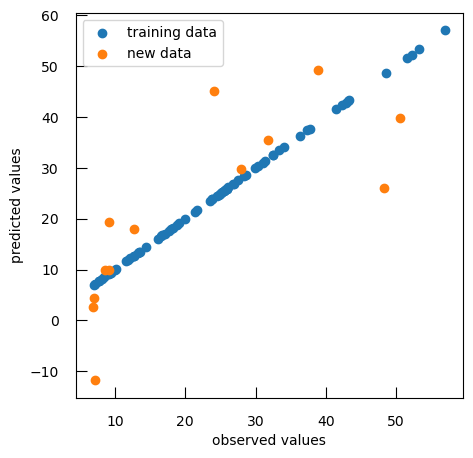

To compare observed values to predicted values, we can generate a scatter plot that visualizes the relationship between observed and predicted values for both training and new data:

plt.scatter(y, y_pred, label="training data")

plt.scatter(ynew, ynew_pred, label="new data")

plt.xlabel("observed values")

plt.ylabel("predicted values")

plt.legend()

As expected, the performance on the new data is not as good as with the data we used to train the model. We have overfitted the data.

Here, we could still use the model that we have created, but we would agree that reporting the perfect performance we had with our training data would be misleading. To honestly report the performance of our model, we measure it on a set of data that has not been used at all to train it: the test set.

To that end, we typically begin by dividing our data into:

- train set to find the best model

- test set to give an honest evaluation of how the model perform on completely new data.

X_test = Xnew

y_test = ynew

Approach 2: Adding regularization and validation set

In the case of a Least Square fit, the function we are minimizing corresponds to the sum of squared difference between the observation and the predictions of our model:

\( \sum_i (y_i-f(\pmb X_i,\pmb{\beta}))^2 \)

with \(y\) the target vector, \(\pmb X\) the input feature matrix and \(f\) our model

Regularization is a way to reduce overfitting. In the case of the linear model we do so by adding to this function a penalization term which depends on coefficient weights. In brief, the stronger the coefficient, the higher the penalization. So only coefficients which bring more fit than penalization will be kept.

The formulas used in scikit-learn functions -other libraries may have a different parameterization, but the concepts stay the same- are:

-

L1 regularization (Lasso): \(\frac{1}{2n}\sum_i (y_i-f(\pmb X_i,\pmb{\beta}))^2 + \alpha\sum_{j}\lvert\beta_{j}\rvert\), with \(\alpha\) being the weight that you put on that regularization

-

L2 regularization (Ridge): \(\sum_i (y_i-f(\pmb X_i,\pmb{\beta}))^2 + \alpha\sum_{j}\beta_{j}^{2}\)

-

Elastic Net: \(\frac{1}{2n}\sum_i (y_i-f(\pmb X_i,\pmb{\beta}))^2 + \alpha\sum_{j}(\rho\lvert\beta_{j}\rvert+\frac{(1-\rho)}{2}\beta_{j}^{2})\)

CommentFor a deeper understanding of those notions, you may look at :

CommentRegularization generalize to maximum likelihood contexts as well

Let’s try that on our data.

We start by importing the SGDRegressor class from the linear_model module of the scikit-learn library. SGDRegressor stands for Stochastic Gradient Descent Regressor. It is an implementation of linear regression that uses Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) to fit the model. SGD is an optimization algorithm that updates the model parameters iteratively based on one sample at a time (or a mini-batch of samples), making it efficient for large datasets. It supports various types of regularization (L1, L2, Elastic Net) to prevent overfitting.

from sklearn.linear_model import SGDRegressor

We would like now to perform a grid search over 50 different values – logarithmically spaced between \(10^{−2}\) and \(10^2\) – of the regularization parameter alpha for an SGDRegressor with L1 penalty (Lasso regression). The results will be stored in a DataFrame for further analysis.

%%time

logalphas = []

coef_dict = {

"name": [],

"coefficient": [],

"log-alpha": [],

}

r2 = []

for alpha in np.logspace(-2, 2, 50):

reg = SGDRegressor(penalty="l1", alpha=alpha)

reg.fit(X , y)

logalphas.append(np.log10(alpha))

r2.append(r2_score(y, reg.predict(X)))

coef_dict["name"] += list(X.columns)

coef_dict["coefficient"] += list(reg.coef_)

coef_dict["log-alpha"] += [np.log10(alpha)]* len(X.columns)

coef_df = pd.DataFrame(coef_dict)

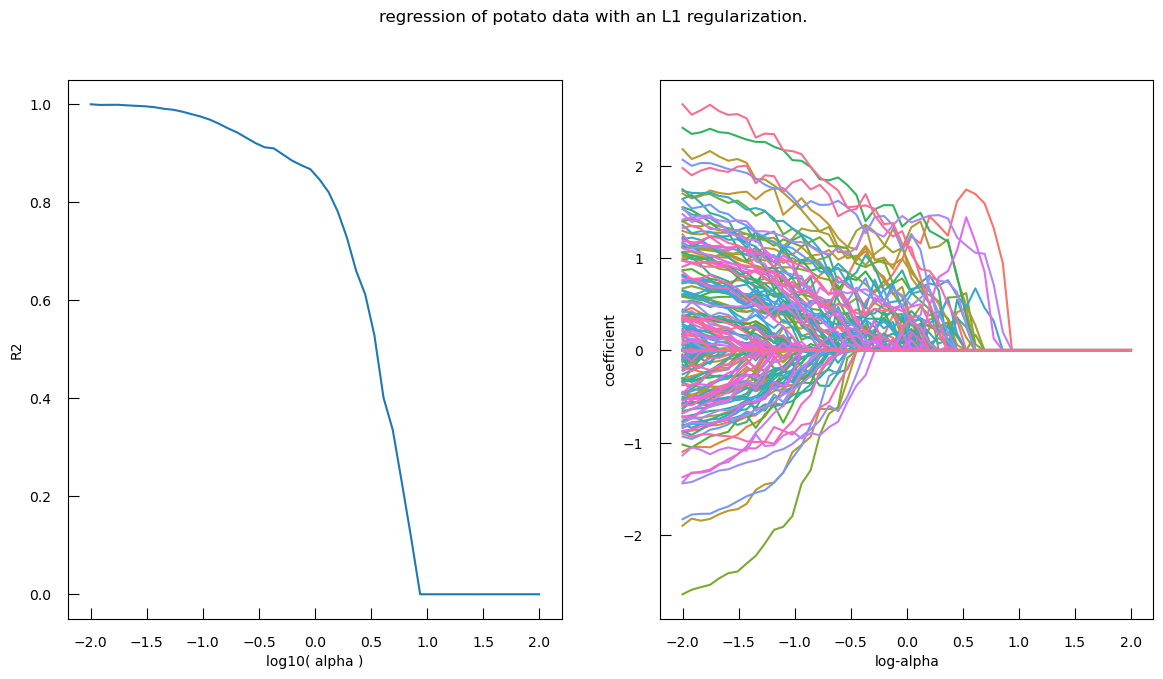

Let’s visualize:

fig,ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(14,7))

ax[0].plot(logalphas, r2)

ax[0].set_xlabel("log10( alpha )")

ax[0].set_ylabel("R2")

sns.lineplot(

x="log-alpha",

y="coefficient",

hue="name",

data=coef_df,

ax=ax[1],

legend = False,

)

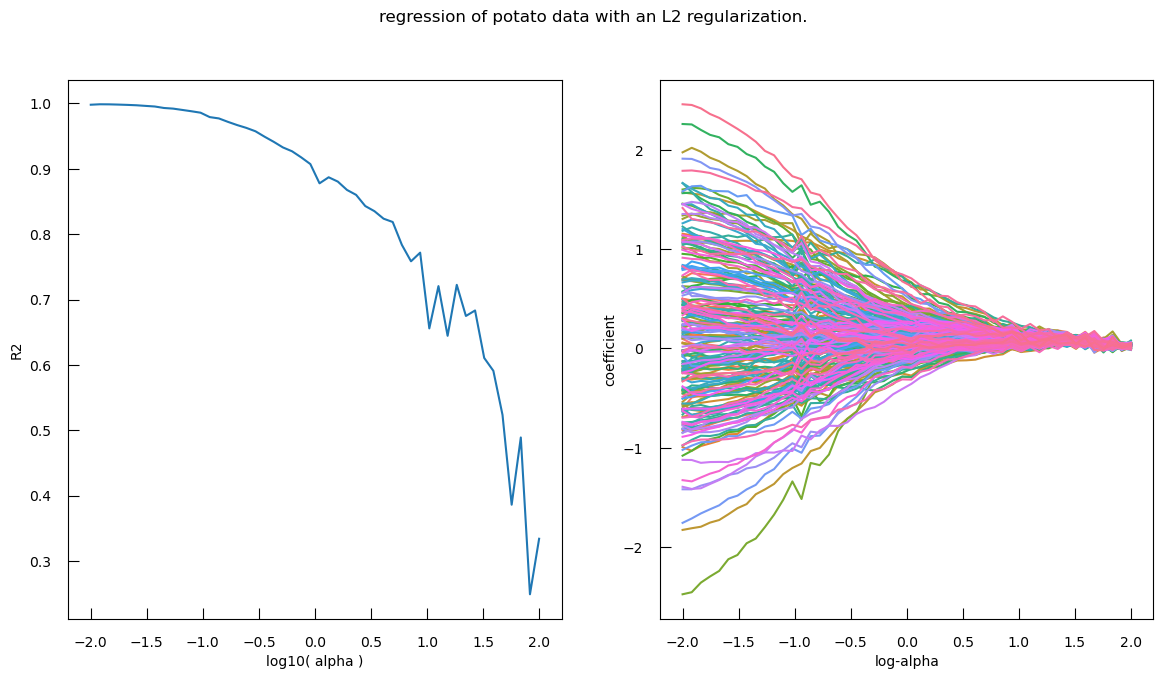

fig.suptitle("Regression of potato data with an L1 regularization.")

Question

- What is in the left subplot?

- How to iterpret the left subplot?

- What is in the right subplot?

- how to iterpret the right subplot?

- The left subplot shows R-squared (\(R^2\)) vs. \(\log10(\alpha)\)

- Interpretation

- High \(R^2\) at Low \(\alpha\): At lower values of \(\log10(\alpha)\) (left side of the plot), the R-squared score is high, indicating that the model fits the data well. This is because the regularization is weak, allowing more features to contribute to the model.

- Sharp Drop in \(R^2\): As \(\log10(\alpha)\) increases, the R-squared score drops sharply. This indicates that stronger regularization (higher alpha values) leads to a simpler model with fewer features, which may not capture the data’s variance as well.

- Optimal Alpha: The point where the R-squared score starts to drop significantly can be considered as the optimal alpha value, balancing model complexity and performance.

- The right subplot shows Coefficients vs. log-alpha

- Interpretation:

- Coefficient Paths: Each colored line represents the path of a coefficient for a specific feature as log-alpha varies.

- Shrinkage to Zero: As log-alpha increases, many coefficients shrink towards zero. This is the effect of L1 regularization, which penalizes the absolute size of the coefficients, leading to sparse models where many coefficients become exactly zero.

- Feature Selection: Features with coefficients that shrink to zero first are less important for the model. Features whose coefficients remain non-zero for higher values of log-alpha are more important.

- Stability: The spread of the lines at lower log-alpha values indicates that the model includes many features. As log-alpha increases, the lines converge, showing that the model becomes simpler and more stable.

Hands OnAdapt the code above to generate this plot with an L2 penalty.

### correction from sklearn.linear_model import SGDRegressor logalphas = [] coef_dict = { "name": [], "coefficient": [], "log-alpha": [], } r2 = [] for alpha in np.logspace(-2, 2, 50): reg = SGDRegressor(penalty="l2", alpha=alpha) reg.fit(X, y) logalphas.append(np.log10(alpha)) r2.append(r2_score(y, reg.predict(X))) coef_dict["name"] += list(X.columns) coef_dict["coefficient"] += list(reg.coef_) coef_dict["log-alpha"] += [np.log10(alpha)]* len(X.columns ) coef_df = pd.DataFrame(coef_dict) fig,ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(14,7)) ax[0].plot(logalphas, r2) ax[0].set_xlabel("log10( alpha )") ax[0].set_ylabel("R2") sns.lineplot( x="log-alpha", y="coefficient", hue="name", data=coef_df, ax = ax[1], legend = False ) fig.suptitle("regression of potato data with an L2 regularization.")Question

- How do each type of regularization affect R-squared (R²)?

- How do each type of regularization affect Coefficients?

- We look at the left Subplot: R-squared (R²) vs. log10(alpha).

- L1 Regularization (Lasso): The R-squared score starts high and remains relatively stable for lower values of log10(alpha), then sharply drops to near zero as log10(alpha) increases. L1 regularization tends to drive many coefficients to exactly zero, effectively performing feature selection. As alpha increases, more features are excluded from the model, leading to a simpler model with fewer features and a sharp drop in R-squared score.

- L2 Regularization (Ridge): The R-squared score starts high and gradually decreases with some fluctuations as log10(alpha) increases. L2 regularization penalizes the squared magnitude of the coefficients, leading to a more gradual shrinkage of coefficients. This results in a smoother decrease in the R-squared score as alpha increases, without the sharp drop seen in L1 regularization.

- Right Subplot: Coefficients vs. log-alpha

- L1 Regularization (Lasso): The coefficient paths show many lines shrinking to zero as log-alpha increases, indicating that many features are excluded from the model. L1 regularization performs feature selection by driving less important feature coefficients to zero. This results in a sparse model where only a few features have non-zero coefficients.

- L2 Regularization (Ridge): The coefficient paths show a more gradual shrinkage towards zero as log-alpha increases, with fewer coefficients becoming exactly zero.L2 regularization retains all features in the model but shrinks their coefficients. This results in a model where all features contribute, but their contributions are reduced.

This is great, but how do we choose which level of regularization we want ?

It is a general rule that as you decrease \(\alpha\), the \(R^2\) on the data used for the fit increase, i.e. you risk overfitting. Consequently, we cannot choose the value of \(\alpha\) parameter from the data used to fit alone. We call such a parameter an hyper-parameter.

QuestionWhat are other hyper-parameters we could optimize at this point?

If we used an Elastic Net penalty, we would also have the L1 ratio to explore

But we could also explore which normalization method we use, which imputation method (if applicable, here that is not the case), and whether we should account for interaction between samples, or degree 2,3,4,… polynomials.

In order to find the optimal value of an hyper-parameter, we separate our training data into:

- a train set used to fit the model

- a validation set used to evaluate how our model perform on new data

Here we have 73 points. we will use 60 points to train the model and the rest to evaluate the model

I = list(range(X.shape[0]))

np.random.shuffle( I )

I_train = I[:60]

I_valid = I[60:]

X_train = X.iloc[I_train, : ]

y_train = y.iloc[I_train]

X_valid = X.iloc[I_valid, : ]

y_valid = y.iloc[I_valid]

We now to train the model with 200 alpha values logarithmically spaced between \(10^{−3}\) and \(10^2\) with L1 penalty (Lasso regression) and make prediction on both the train and validation sets:

logalphas = []

r2_train = []

r2_valid = []

for alpha in np.logspace(-3, 2, 200):

reg = SGDRegressor(penalty="l1", alpha=alpha)

reg.fit(X_train, y_train)

logalphas.append(np.log10(alpha))

r2_train.append(r2_score(y_train, reg.predict(X_train)))

r2_valid.append(r2_score(y_valid, reg.predict(X_valid)))

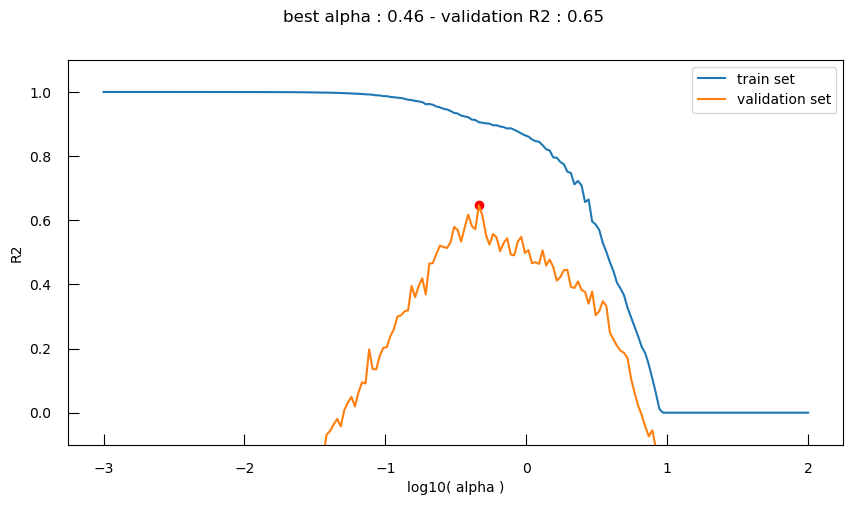

Let’s visualize the \(R^2\) for both the train and validation sets, as well as the \(\alpha\) value with highest \(R^2\) for the validation set:

bestI = np.argmax(r2_valid)

bestLogAlpha = logalphas[bestI]

bestR2_valid = r2_valid[bestI]

fig,ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10,5))

fig.suptitle(f"best alpha : {10**bestLogAlpha:.2f} - validation R2 : {bestR2_valid:.2f}")

ax.plot(logalphas, r2_train, label="train set")

ax.plot(logalphas, r2_valid, label="validation set")

ax.scatter([bestLogAlpha], [bestR2_valid], c="red")

ax.set_xlabel("log10( alpha )")

ax.set_ylabel("R2")

ax.set_ylim(-0.1, 1.1)

ax.legend()

So now, with the help of the validation set, we can clearly see different phases:

- Underfitting: for high \(\alpha\), the performance is low for both the train and the validation set

- Overfitting: for low \(\alpha\), the performance is high for the train set, and low for the validation set

We want the equilibrium point between the two where performance is ideal for the validation set. But if we run the code above several time, we will see that the optimal point varies due to the random assignation to train or validation set.

There exists a myriad of possible strategies to deal with that problem, such as repeating the above many times and taking the average of the results for instance.

CommentThis problem gets less important as the validation set size increases.

Anyhow, on top of our earlier regression model, we have added:

- an hyper-parameter : \(\alpha\), the strength of the regularization term

- a validation strategy for our model in order to avoid overfitting

That’s it, we are now in the world of Machine Learning. But how does the modified model perform on the test data?

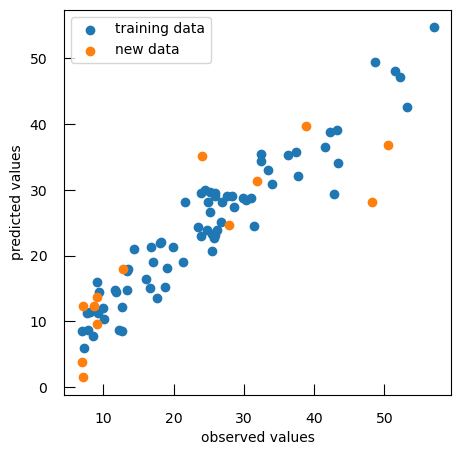

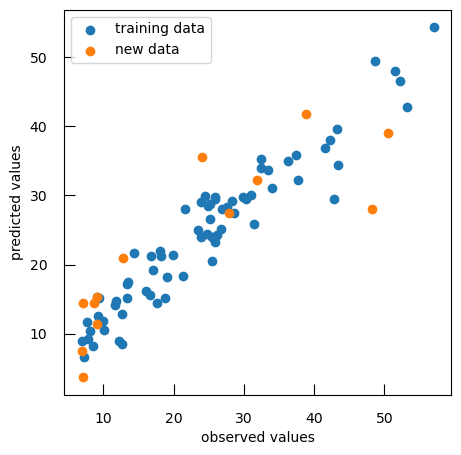

Hands OnCheck how the modified model performs on the test data

reg = SGDRegressor(penalty="l1", alpha = 10**bestLogAlpha) reg.fit( X , y ) y_pred = reg.predict( X ) print(f"train data R-squared score: { r2_score(y, y_pred ) :.2f}") print(f"train data mean squared error: { mean_squared_error(y, y_pred ) :.2f}") y_test_pred = reg.predict( X_test ) print(f"test data R-squared score: { r2_score(y_test, y_test_pred ) :.2f}") print(f"test data mean squared error: { mean_squared_error(y_test, y_test_pred ) :.2f}") plt.scatter(y, y_pred, label="training data" ) plt.scatter(y_test, y_test_pred, label="new data" ) plt.xlabel("observed values") plt.ylabel("predicted values") plt.legend()QuestionWhat are the R-squared score and mean squared error for both training and test data?

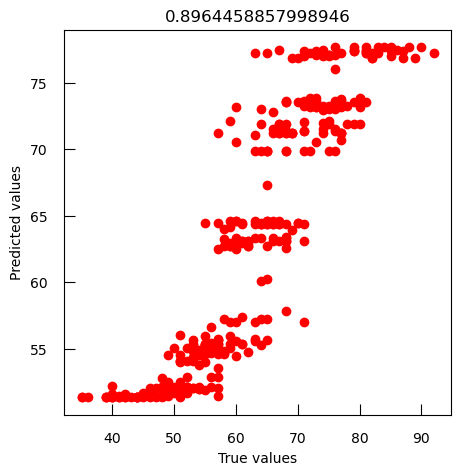

Data R-squared score mean squared error Training 0.90 15.81 Test 0.73 65.83

Two things we can observe:

- Still better performance on the train data than on the test data (generally always the case)

- the performance on the test set has improved: our model is less overfit and more generalizable

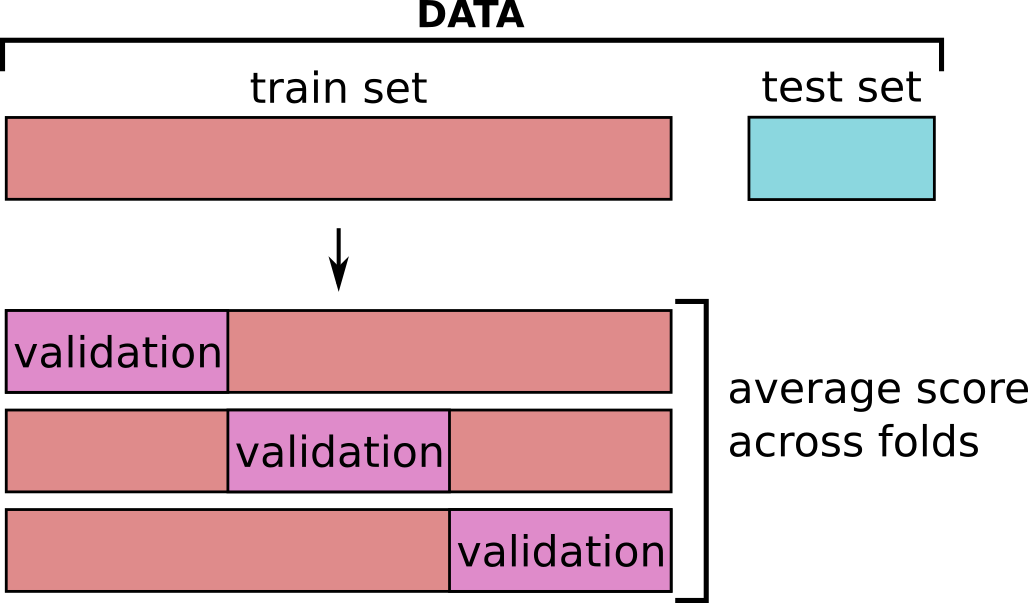

Approach 3: k-fold cross-validation

In the previous approach, we have split our training data into a train set and a validation set. This approach works well if you have enough data for your validation set to be representative. Often, we unfortunately do not have enough data for this.

Indeed, we have seen that if we run the code above several time, we see that the optimal point varies due to the random assignation to train or validation set. k-fold cross validation is one of the most common strategy to try to mitigate this randomness with a limited amount of data.

In k-fold cross-validation,

- Data is split in \(k\) subpart, called fold.

- \(k\) models are trained for a given hyper-parameter values combination: each time a different fold is used for validation (and the remaining \(k-1\) folds for training).

- The average performance is computed across all fold : this is the cross-validated performance.

Let’s do a simple k-fold manually once (with \(k = 5\)) to explore how it works:

from sklearn.model_selection import KFold

kf = KFold(n_splits=5, shuffle=True, random_state=734)

for i, (train_index, valid_index) in enumerate(kf.split(X)):

print(f"Fold {i}:")

print(f" Train: index={train_index}")

print(f" Test: index={valid_index}")

QuestionFold 0: Train: index=[ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 17 18 19 20 21 22 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 33 34 35 39 40 41 45 46 47 48 50 51 53 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 72] Test: index=[ 8 16 23 32 36 37 38 42 43 44 49 52 54 70 71] Fold 1: Train: index=[ 4 5 6 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 18 19 20 21 23 24 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 42 43 44 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 70 71] Test: index=[ 0 1 2 3 7 17 22 25 40 41 45 55 68 69 72] Fold 2: Train: index=[ 0 1 2 3 4 6 7 8 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 47 48 49 52 53 54 55 57 59 61 64 65 68 69 70 71 72] Test: index=[ 5 9 28 29 30 46 50 51 56 58 60 62 63 66 67] Fold 3: Train: index=[ 0 1 2 3 5 6 7 8 9 12 14 16 17 19 20 22 23 25 28 29 30 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 49 50 51 52 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 66 67 68 69 70 71 72] Test: index=[ 4 10 11 13 15 18 21 24 26 27 31 48 53 65] Fold 4: Train: index=[ 0 1 2 3 4 5 7 8 9 10 11 13 15 16 17 18 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 36 37 38 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 58 60 62 63 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72] Test: index=[ 6 12 14 19 20 33 34 35 39 47 57 59 61 64]Do you have the same indexes for train and test sets in each fold as above? How is it possible?

The indexes for train and test sets in each fold are the same because the random state was fixed.

In practice that it is mostly automatized with some of scikit-learn’s recipes and objects:

- Setting up the range of \(\alpha\) values

- Setting up k-fold cross-validation as above

- Looping over \(\alpha\) values and over each fold in the k-fold cross-validation:

- Splits the data into training and validation sets.

- Fits the

SGDRegressormodel with the current \(\alpha\) value on the training set. - Evaluates the model on the validation set using the \(R^{2}\) score.

- Stores the \(R^{2}\) score for the current fold and updates the average \(R^{2}\) score across all folds.

- Finding the best \(\alpha\) value

%%time

logalphas = np.linspace(-2, 1, 200)

kf = KFold(n_splits=5, shuffle=True, random_state=6581)

fold_r2s = [[] for i in range(kf.n_splits)] ## for each fold

cross_validated_r2 = [] # average across folds

for j,alpha in enumerate( 10**logalphas ) :

cross_validated_r2.append(0)

for i, (train_index, valid_index) in enumerate(kf.split(X)):

## split train and validation sets

X_train = X.iloc[train_index, : ]

X_valid = X.iloc[valid_index, : ]

y_train = y.iloc[train_index]

y_valid = y.iloc[valid_index]

## fit model for that fold

reg = SGDRegressor(penalty="l1", alpha = alpha)

reg.fit(X_train, y_train )

## evaluate for that fold

fold_score = r2_score(y_valid, reg.predict(X_valid))

## keeping in the curve specific to this fold

fold_r2s[i].append(fold_score)

## keeping a tally of the average across folds

cross_validated_r2[-1] += fold_score/kf.n_splits

bestI = np.argmax(cross_validated_r2)

bestLogAlpha = logalphas[bestI]

bestR2_valid = cross_validated_r2[bestI]

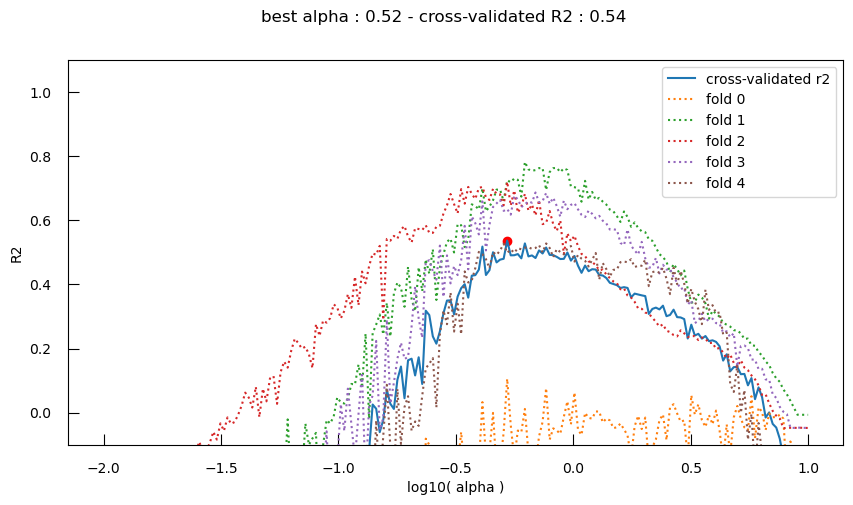

Let’s now plot the cross-validated performance of an SGDRegressor model with L1 regularization (\(R^{2}\)) across the different \(\alpha\) values:

fig,ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10,5))

ax.plot(logalphas, cross_validated_r2, label="cross-validated r2")

ax.scatter([bestLogAlpha] , [bestR2_valid], c="red")

for i,scores in enumerate(fold_r2s):

ax.plot(logalphas, scores, label=f"fold {i}", linestyle="dotted")

ax.set_xlabel("log10( alpha )")

ax.set_ylabel("R2")

ax.set_ylim(-0.1, 1.1)

ax.legend()

fig.suptitle(f"best alpha : {10**bestLogAlpha:.2f} - cross-validated R2 : {bestR2_valid:.2f}")

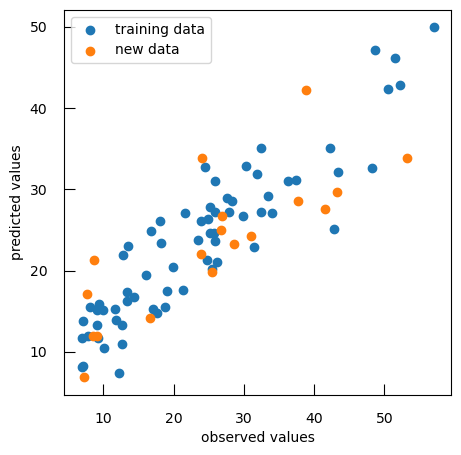

Hands OnRe-fit a model with the best \(\alpha\) above (\(\alpha = 0.52\)) and check the performance with the test data

reg = SGDRegressor(penalty="l1", alpha = 10**bestLogAlpha) reg.fit(X, y ) y_pred = reg.predict(X) print(f"train data R-squared score: { r2_score(y, y_pred ) :.2f}") print(f"train data mean squared error: { mean_squared_error(y, y_pred ) :.2f}") y_test_pred = reg.predict(X_test) print(f"test data R-squared score: { r2_score(y_test, y_test_pred ) :.2f}") print(f"test data mean squared error: { mean_squared_error(y_test, y_test_pred ) :.2f}") plt.scatter(y, y_pred, label="training data" ) plt.scatter(y_test, y_test_pred, label="new data" ) plt.xlabel("observed values") plt.ylabel("predicted values") plt.legend()Question

- What are the R-squared score and mean squared error for both training and test data?

- What can we conclude from the plot?

R-squared score and mean squared error for both training and test data:

Data R-squared score mean squared error Training 0.90 14.99 Test 0.72 69.05 There are some deviations, especially for the new data points, suggesting areas where the model’s predictions may need improvement.

There, you can realize that now, for each possible value of our hyper-parameter we fit and evaluate not 1, but $k$ models, here 4. So, for 200 values of \(\alpha\), that means \(200 x 5 = 1000\) models to fit and evaluate.

Now, consider that we have other hyper-parameters, such as the type of regularization (L1 or L2), or how we perform scaling, or whether we consider interactions, and now you understand why Machine Learning can quickly become computationnaly intensive.

Approach 4: “classical” ML pipeline

Let’s start back from scratch to recapitulate what we have seen and use scikit-learn to solve the potato problem:

-

Get the full dataset (86 potatoes instead of 73):

X = dfTT y = df["Flesh Colour"] -

Split our data in a train and a test set using

train_test_splitfromscikit-learnwith the idea that 20% of the data will be used for testing, and the remaining 80% will be used for training.from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2) print(f"train set size: {len(y_train)}") print(f"test set size: {len(y_test)}")QuestionWhat are the sizes of the train and test sets?

train set size: 68

test set size: 18

-

Train a model while optimizing some hyper-parameters.

On top of what we’ve done before, we would like to add a scaling phase and test L1 or L2 penalties. The scaling phase is a crucial preprocessing step where the features of your dataset are transformed to a standard scale. This step is important for several reasons: it improves model performance, prevents the dominance of large-range features, and ensures convergence, especially for algorithms that use optimization techniques like gradient descent. Common scaling techniques include standardization (Z-score normalization), which scales the features to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, and min-max scaling (normalization), which scales the features to a fixed range, usually between 0 and 1.

Scikit-learn’s GridSearchCV is useful to explore these more “complex” hyper-parameter spaces. Let’s see how to set up a machine learning pipeline with scaling and linear regression using StandardScaler and SGDRegressor, and how to use GridSearchCV to explore different hyperparameter combinations, after that X_train and y_train have been defined as training features and labels.

-

Create the pipeline with two steps: scaling (set mean of each feature at 0 and (optionally) standard dev at 1 ) and linear regression with regularization

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline pip_reg = Pipeline([ ("scaler", StandardScaler()), # Standard scaling step ("model", SGDRegressor()), # Linear regression model with regularization ]) -

Define the hyperparameters and their ranges to be tested

grid_values = { "scaler__with_std": [True, False], # Whether to scale to unit variance (standard deviation of 1) "model__penalty": ["l1", "l2"], # L1 or L2 regularization "model__alpha": np.logspace(-2, 2, 200), # Regularization strength }Question- What is the data structure to define the hyperparameters and their range?

- What is the specificity for hyperparameter names?

- The data structure is a dictionary with hyperparameter name as keys and values being the set of values to explore.

- The hyperparameter names use a double underscore

-

Set up

GridSearchCVwith the pipeline, parameter grid (all available CPU cores), scoring metric (i.e. \(R^{2}\)), and cross-validation strategy (i.e. 5-fold)from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV grid_reg = GridSearchCV( pip_reg, param_grid=grid_values, scoring="r2", cv=5, n_jobs=-1, ) -

Fit the

GridSearchCVobject to the training dataThe gridSearchCV object will go through each hyperparameter value combination and fit and evaluate each fold, and averages the score across each fold. It then finds the combination that gave the best score and use it to re-train a model with the whole train data

grid_reg.fit(X_train, y_train) -

Get the best cross-validated score

print(f"Grid best score ({grid_reg.scoring}): {grid_reg.best_score_:.3f}") print("Grid best parameter :") for k,v in grid_reg.best_params_.items(): print(f" {k:>20} : {v}")Question- What is the grid best score?

- What is the grid best parameter?

- 0.667

- \(\alpha = 6.5173\) with L2 penalty and scale to unit variance

Let’s re-fit a model with the best hyperparameter values and check the performance with the test data:

reg = grid_reg.best_estimator_

y_pred = reg.predict(X_train)

print(f"train data R-squared score: { r2_score(y_train, y_pred) :.2f}")

print(f"train data mean squared error: { mean_squared_error(y_train, y_pred) :.2f}")

y_test_pred = reg.predict(X_test)

print(f"test data R-squared score: { r2_score(y_test, y_test_pred) :.2f}")

print(f"test data mean squared error: { mean_squared_error(y_test, y_test_pred) :.2f}")

plt.scatter(y_train, y_pred, label="training data")

plt.scatter(y_test, y_test_pred, label="new data")

plt.xlabel("observed values")

plt.ylabel("predicted values")

plt.legend()

Question

- What are the R-squared score and mean squared error for both training and test data?

- What can we conclude from the plot?

R-squared score and mean squared error for both training and test data:

Data R-squared score mean squared error Training 0.80 32.03 Test 0.59 74.11 The new data look much better. But, there is still some scatter, indicating variability in prediction

One can also access the best model parameter:

pd.DataFrame(grid_reg.cv_results_)

| mean_fit_time | std_fit_time | mean_score_time | std_score_time | param_model__alpha | param_model__penalty | param_scaler__with_std | params | split0_test_score | split1_test_score | split2_test_score | split3_test_score | split4_test_score | mean_test_score | std_test_score | rank_test_score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.032404 | 0.003947 | 0.007624 | 0.003920 | 0.010000 | l1 | True | {'model__alpha': 0.01, 'model__penalty': 'l1',... |

0.458166 | 0.426002 | 0.598553 | 0.090676 | -0.436497 | 0.227380 | 0.371457 | 674 |

| 1 | 0.037641 | 0.002405 | 0.009909 | 0.007381 | 0.010000 | l1 | False | {'model__alpha': 0.01, 'model__penalty': 'l1',... |

0.489853 | 0.463623 | 0.608050 | 0.140120 | -0.382414 | 0.263847 | 0.358448 | 603 |

| 2 | 0.020803 | 0.001697 | 0.006123 | 0.000453 | 0.010000 | l2 | True | {'model__alpha': 0.01, 'model__penalty': 'l2',... |

0.464953 | 0.451351 | 0.597122 | 0.102295 | -0.413050 | 0.240534 | 0.365580 | 644 |

| 3 | 0.021677 | 0.001587 | 0.006235 | 0.000385 | 0.010000 | l2 | False | {'model__alpha': 0.01, 'model__penalty': 'l2',... |

0.491105 | 0.472125 | 0.606778 | 0.147489 | -0.362163 | 0.271067 | 0.351509 | 579 |

| 4 | 0.035426 | 0.003058 | 0.006576 | 0.001052 | 0.010474 | l1 | True | {'model__alpha': 0.010473708979594498, 'model_... |

0.456685 | 0.432716 | 0.601580 | 0.102170 | -0.437758 | 0.231079 | 0.372233 | 663 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| 795 | 0.009917 | 0.000802 | 0.004006 | 0.000370 | 95.477161 | l2 | False | {'model__alpha': 95.47716114208056, 'model__pe... |

0.447653 | 0.376443 | 0.497583 | 0.281709 | 0.374550 | 0.395588 | 0.073337 | 389 |

| 796 | 0.020417 | 0.001838 | 0.005503 | 0.002358 | 100.000000 | l1 | True | {'model__alpha': 100.0, 'model__penalty': 'l1'... |

-0.011842 | -0.015431 | -0.072717 | -0.000012 | -0.305135 | -0.081028 | 0.114845 | 767 |

| 797 | 0.019441 | 0.001637 | 0.004185 | 0.000180 | 100.000000 | l1 | False | {'model__alpha': 100.0, 'model__penalty': 'l1'... |

-0.011947 | -0.015128 | -0.071826 | -0.000032 | -0.303618 | -0.080510 | 0.114284 | 712 |

| 798 | 0.010385 | 0.001114 | 0.004745 | 0.000793 | 100.000000 | l2 | True | {'model__alpha': 100.0, 'model__penalty': 'l2'... |

0.284024 | 0.397677 | 0.350576 | 0.233945 | -0.024301 | 0.248384 | 0.147355 | 625 |

| 799 | 0.008413 | 0.000895 | 0.002982 | 0.000690 | 100.000000 | l2 | False | {'model__alpha': 100.0, 'model__penalty': 'l2'... |

0.159616 | 0.416827 | 0.200832 | 0.211811 | 0.054615 | 0.208740 | 0.117932 | 678 |

QuestionWhat are the columns in the outputs?

mean_fit_time: The mean time taken to fit the model for each set of hyperparameters.std_fit_time: The standard deviation of the fit times for each set of hyperparameters.mean_score_time: The mean time taken to score the model for each set of hyperparameters.std_score_time: The standard deviation of the score times for each set of hyperparameters.param_model__penalty:param_scaler__with_std:params: A dictionary containing the combination of hyperparameters used in each iteration of the grid search.split<split_id>_test_score: The test score for each individual split in the cross-validation.mean_test_score: The mean cross-validation score for each set of hyperparameters. This is the primary metric used to evaluate the performance of the model.std_test_score: The standard deviation of the cross-validation scores for each set of hyperparameters. This gives an idea of the variability in the model’s performance.rank_test_scores: The rank of the test scores for each set of hyperparameters, where 1 is the best.

To get the best-performing model from a grid search, already fitted with the optimal hyperparameters:

best_model = grid_reg.best_estimator_

best_model

QuestionWhat is the \(\alpha\) value for the model?

6.5173

Let’s now to access the coefficients of the model:

coefficients = best_model.coef_

coefficients

Question

- How many coefficients are there?

- What do these coefficients represents?

- How do you interpret the values?

- 200

- They represent the weights that the model has learned to associate with each feature in the dataset, i.e. gene expression. These coefficients indicate the contribution of each gene to the prediction of the target variable.

- Interpretation of coefficients:

- Magnitude: The magnitude (absolute value) of a coefficient indicates the strength of the relationship between the corresponding feature and the target variable. Larger magnitudes suggest that the feature has a stronger influence on the prediction.

- Sign: The sign of a coefficient indicates the direction of the relationship between the feature and the target variable. A positive coefficient indicates a positive relationship, meaning that as the feature value increases, the target variable also increases. A negative coefficient indicates a negative relationship, meaning that as the feature value increases, the target variable decreases.

- Feature Importance: In the context of regularization (L1 or L2), the coefficients also reflect the importance of each feature.

- With L1 regularization (Lasso), some coefficients may be exactly zero, indicating that the corresponding features are not important and are excluded from the model.

- With L2 regularization (Ridge), all coefficients are typically non-zero but may be shrunk towards zero, indicating the relative importance of each feature.

We have explored the fundamentals of linear regression, including how to fit models, evaluate their performance, and interpret coefficients, it’s time to shift our focus to another essential technique in Machine Learning: logistic regression.

Logistic regression

Simple case

Let’s imagine a simple case with 2 groups, and a single feature:

X1 = np.concatenate([np.random.randn(300), np.random.randn(300)+4])

y = np.array([0]*300 + [1]*300)

sns.histplot(x=X1, hue=y)

We will use a logistic regression to model the relationship between the class and the feature. While linear regression is used for predicting continuous outcomes, logistic regression is specifically designed for classification problems, where the goal is to predict categorical outcomes. Logistic regression does not model the class directly, but rather model the class probabilities (through the logit transform).

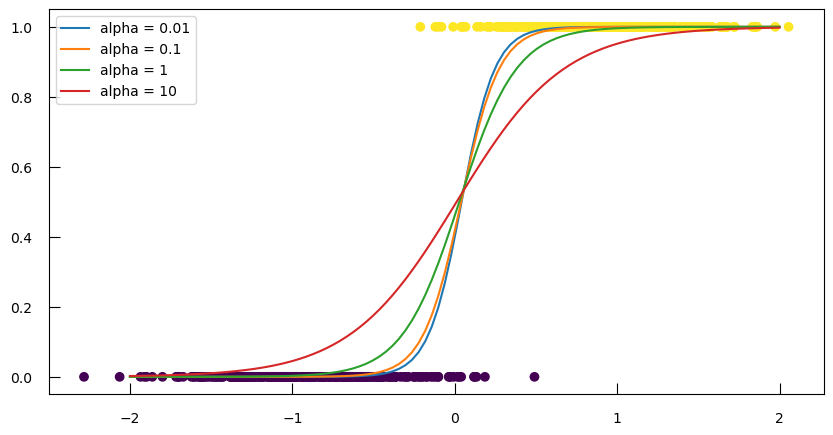

Let’s see how effect of different regularization strengths (alpha values) on the class probabilities predicted by a logistic regression model:

-

Scale the feature data

X1usingStandardScalerto ensure that the data has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Scaling is important for logistic regression to ensure that all features contribute equally to the model.X1_norm = StandardScaler().fit_transform(X1.reshape(X1.shape[0], 1)) -

Loop over \(\alpha\) values to

- Initialize and fit a

LogisticRegressionmodel with L2 penalty to the scaled data. - Calculate and plot the predicted probabilities for class 1 over a range of values from -2 to 2.

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10,5)) ax.scatter(X1_norm, y, c=y) for alpha in [0.01, 0.1, 1, 10]: # this implementation does not take alpha but rather C = 1/alpha C = 1/alpha lr = LogisticRegression(penalty="l2", C=C) lr.fit(X1_norm, y) proba = lr.predict_proba(np.linspace(-2, 2, 100).reshape(-1, 1)) ax.plot(np.linspace(-2, 2, 100), proba[:,1], label=f"alpha = {alpha}") ax.legend() - Initialize and fit a

We can see that when \(\alpha\) grows, the probabilities evolve more smoothly, i.e. we have more regularization. However, note that all the curves meet at the same point, corresponding to the 0.5 probability. This is nice, but our end-goal is to actually be able to predict the classes, and not just the probabilities.

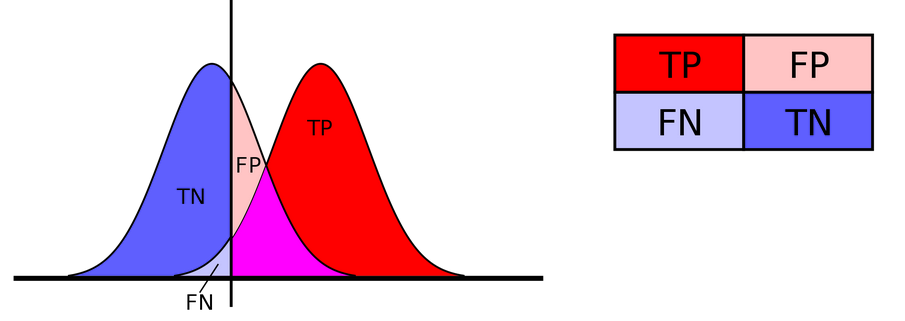

Our task is not regression anymore, but rather classification. So here, we should not evaluate the model using \(R^2\) or log-likelihood, but a classification metric.

Let’s begin by the most common: Accuracy, i.e. the proportion of samples which were correctly classified (as either category):

\[Accuracy = \frac{TP + TN}{TP+FP+FN+TN}\]with

- TP: True Positive

- FP: False Positive

- TN: True Negative

- FN: False Negative

Open image in new tab

Open image in new tabAccuracy forces us to make a choice about the probability threshold we use predict categories. 0.5 is a common choice, and the default of the predict method:

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

y_predicted = lr.predict(X1_norm)

print(f"Accuracy with a threshold of 0.5 : {accuracy_score(y, y_predicted):.2f}" )

QuestionWhat is the accuracy with a threshold of 0.5?

0.98

Let’s look at the cross-tabulation:

pd.crosstab(y, y_predicted, rownames=["observed"], colnames=["predicted"])

| predicted | 0 | 1 |

|---|---|---|

| observed | ||

| 0 | 292 | 8 |

| 1 | 5 | 295 |

QuestionUsing this cross-tabulation, how many

- True Positives (TP)

- True Negatives (TN)

- False Positives (FP)

- False Negatives (FN)

are there?

- True Positives (TP): The number of instances where the actual class is 1 and the predicted class is also 1. Here, TP = 295.

- True Negatives (TN): The number of instances where the actual class is 0 and the predicted class is also 0. Here, TN = 292.

- False Positives (FP): The number of instances where the actual class is 0 but the predicted class is 1. Here, FP = 8.

- False Negatives (FN): The number of instances where the actual class is 1 but the predicted class is 0. Here, FN = 5.

But it can be useful to remember that this is only 1 choice among many:

y_predicted

In logistic regression, the default decision threshold is 0.5, but we can adjust it the accuracy.

threshold = 0.2

y_predicted = lr.predict_proba(X1_norm)[:, 1] > threshold

print(f"Accuracy with a threshold of {threshold} : {accuracy_score(y,y_predicted):.2f}")

pd.crosstab(y, y_predicted, rownames=["observed"], colnames=["predicted"])

When the threshold of 0.2, the accuracy is 0.92. The cross-tabulation is:

| predicted | 0 | 1 |

|---|---|---|

| observed | ||

| 0 | 254 | 46 |

| 1 | 0 | 300 |

QuestionWhen you modify the threhold in the code above:

- in which direction should the threshold move to limit the number of False Positive ?

- for which application could that be useful ?

To limit the number of False Positive you need to increase the threshold (a higher threshold means that you only predict cases where you have a higher certainty in positive prediction).

Applications where a false positive would incur a very high cost : eligibility for risky surgery for example, predicting mushroom edibility

Breast tumor dataset

Let’s build a logistic regression model that will be able to predict if a breast tumor is malignant or not.

-

Get the dataset that is in

sklearn.datasetsfrom sklearn.datasets import load_breast_cancer data = load_breast_cancer()Question- How features are in data (

data["feature_names"])? - What are the features?

- 30

- ‘mean radius’, ‘mean texture’, ‘mean perimeter’, ‘mean area’, ‘mean smoothness’, ‘mean compactness’, ‘mean concavity’, ‘mean concave points’, ‘mean symmetry’, ‘mean fractal dimension’, ‘radius error’, ‘texture error’, ‘perimeter error’, ‘area error’,’smoothness error’, ‘compactness error’, ‘concavity error’, ‘concave points error’, ‘symmetry error’, ‘fractal dimension error’, ‘worst radius’, ‘worst texture’, ‘worst perimeter’, ‘worst area’, ‘worst smoothness’, ‘worst compactness’, ‘worst concavity’, ‘worst concave points’, ‘worst symmetry’, ‘worst fractal dimension’

- How features are in data (

-

Keep only the feature statring with

meanto complexify the problemm = list(map(lambda x : x.startswith("mean "), data["feature_names"])) X_cancer = data["data"][:,m] y_cancer = 1-data["target"]Question- How many features have been kept?

- Create a dataframe

X_cancerand add an extra columntargetwith the content ofy_cancer. How does the head the dataframe look like? - How many benign (0 for target) and malign (1) samples do we have?

- 10

-

Dataframe creation

breast_cancer_df=pd.DataFrame(X_cancer, columns=data["feature_names"][m]) breast_cancer_df["target"] = y_cancer breast_cancer_df.head()mean radius mean texture mean perimeter mean area mean smoothness mean compactness mean concavity mean concave points mean symmetry mean fractal dimension target 0 17.99 10.38 122.80 1001.0 0.11840 0.27760 0.3001 0.14710 0.2419 0.07871 1 1 20.57 17.77 132.90 1326.0 0.08474 0.07864 0.0869 0.07017 0.1812 0.05667 1 2 19.69 21.25 130.00 1203.0 0.10960 0.15990 0.1974 0.12790 0.2069 0.05999 1 3 11.42 20.38 77.58 386.1 0.14250 0.28390 0.2414 0.10520 0.2597 0.09744 1 4 20.29 14.34 135.10 1297.0 0.10030 0.13280 0.1980 0.10430 0.1809 0.05883 1 -

We need to get the number of 0 and 1 values in

target:breast_cancer_df.target.value_counts()There are:

- 357 benign samples

- 212 malignant samples

Here, all these covariables / features are defined on very different scales, for them to be treated fairly in their comparison you need to take that into account by scaling.

Hands On: Logistic regression to detect breast cancer malignancy

Split the data into a train and a test dataset by complete the following code cell:

# stratify is here to make sure that you split keeping the repartition of labels unaffected X_train_cancer, X_test_cancer, y_train_cancer, y_test_cancer = ... print(f"fraction of class malignant in train {sum(y_train_cancer)/len(y_train_cancer)}") print(f"fraction of class malignant in test {sum(y_test_cancer)/len(y_test_cancer)}") print(f"fraction of class malignant in full {sum(y_cancer)/len(y_cancer)}")X_train_cancer, X_test_cancer, y_train_cancer, y_test_cancer = train_test_split( X_cancer, y_cancer, random_state=0, stratify=y_cancer ) print(f"fraction of class malignant in train {sum(y_train_cancer)/len(y_train_cancer)}") print(f"fraction of class malignant in test {sum(y_test_cancer)/len(y_test_cancer)}") print(f"fraction of class malignant in full {sum(y_cancer)/len(y_cancer)}")QuestionWhat is the fraction of malignant samples in

- train set?

- test set?

- full set?

- 0.3732394366197183

- 0.3706293706293706

- 0.37258347978910367

Design the pipeline and hyper-parameter grid search with the following specification:

- hyperparameters:

- scaler : no hyper-parameters for the scaler (ie, we will keep the defaults)

- logistic regression : test different values for

Candpenalty- score: “accuracy”

- cross-validation: use 10 folds

Comment: Elastinet penaltyIf you want to test the elasticnet penalty, you will also have to adapt the

solverparameter (cf. the LogisticRegression documentation )%%time pipeline_lr_cancer = Pipeline([ ("scaler", StandardScaler()), ("model", LogisticRegression(solver="liblinear")), ]) # Hyper-parameter space to explore grid_values = {...} # GridSearchCV object grid_cancer = GridSearchCV(...) # Pipeline training grid_cancer.fit(...) # Best cross-validated score print(f"Grid best score ({grid_cancer.scoring}): {grid_cancer.best_score_:.3f}") # Best parameters print("Grid best parameter:") for k,v in grid_cancer.best_params_.items(): print(f" {k:>20} : {v}")pipeline_lr_cancer = Pipeline([ ("scaler", StandardScaler()), ("model", LogisticRegression(solver="liblinear")), ]) # Hyper-parameter space to explore grid_values = { "model__C": np.logspace(-5, 2, 100), "model__penalty":["l1", "l2"] } # GridSearchCV object grid_cancer = GridSearchCV( pipeline_lr_cancer, param_grid=grid_values, scoring="accuracy", cv=10, n_jobs=-1, ) # Pipeline training grid_cancer.fit(X_train_cancer, y_train_cancer) # Best cross-validated score print(f"Grid best score ({grid_cancer.scoring}): {grid_cancer.best_score_:.3f}") # Best parameters print("Grid best parameter:") for k,v in grid_cancer.best_params_.items(): print(f" {k:>20} : {v}")Question

- What is the best score (accuracy)?

- What are the best parameters?

- 0.946

- model__C : 0.0210490414451202, model__penalty : l2

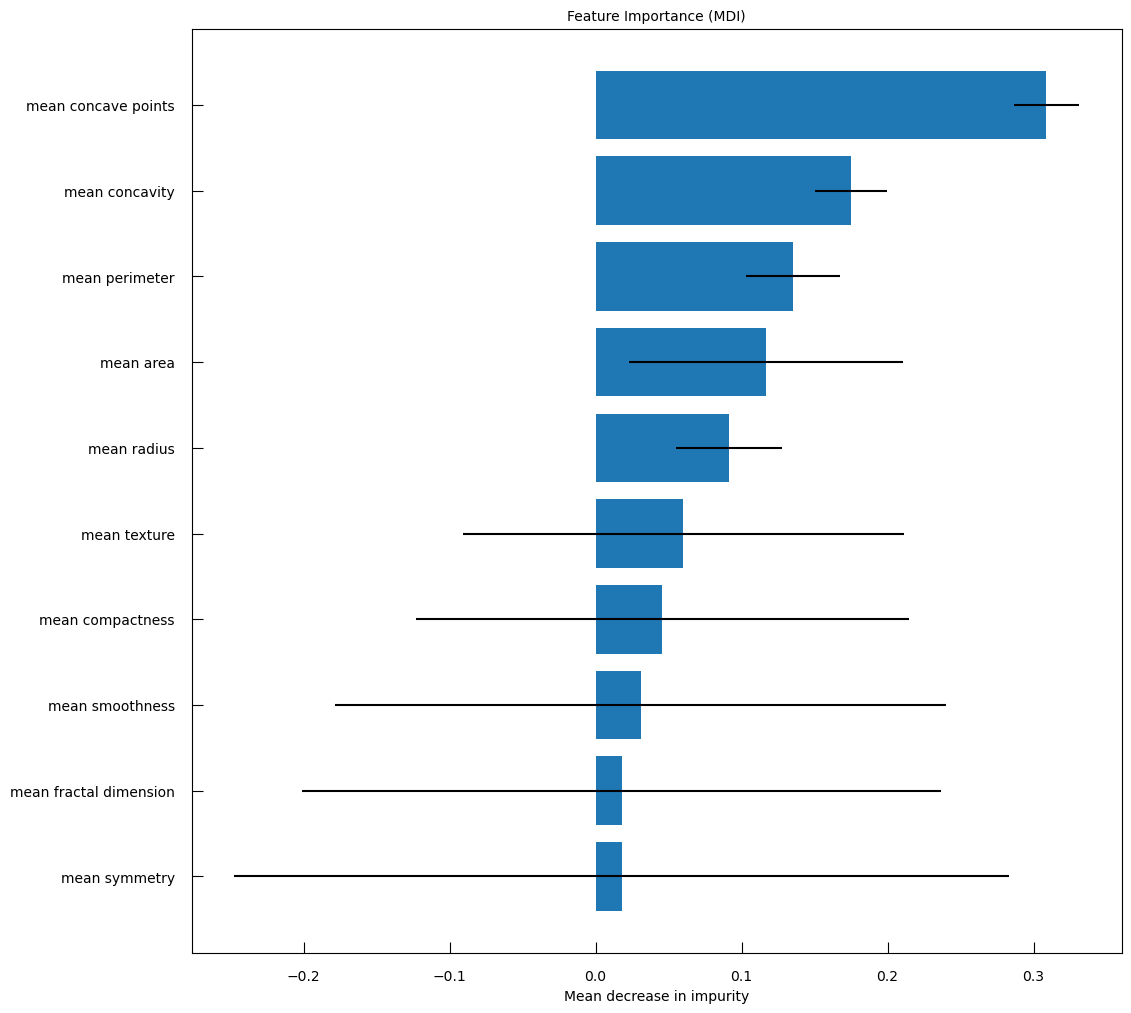

From there we can explore the model a bit further. We can access the coefficient of the model and sort them to assess their importance:

w_lr_cancer = grid_cancer.best_estimator_["model"].coef_[0]

sorted_features = sorted(

zip(breast_cancer_df.columns, w_lr_cancer),

key=lambda x : np.abs(x[1]), # sort by absolute value

reverse=True,

)

print("Features sorted per importance in discriminative process")

for f, ww in sorted_features:

print(f"{f:>25}\t{ww:.3f}")

QuestionWhich features are the most important in the discriminative process?

Features sorted per importance in discriminative process

Feature Coefficient mean concave points 0.497 mean radius 0.442 mean perimeter 0.441 mean area 0.422 mean concavity 0.399 mean texture 0.373 mean compactness 0.295 mean smoothness 0.264 mean symmetry 0.183 mean fractal dimension -0.070 The mean tumor concave points, i.e. the number of concave portions of the tumor contour, the mean tumor radius, the mean tumor perimeter, the mean tumor area have coefficient above 0.4. It means that higher the values, higher the gene expression.

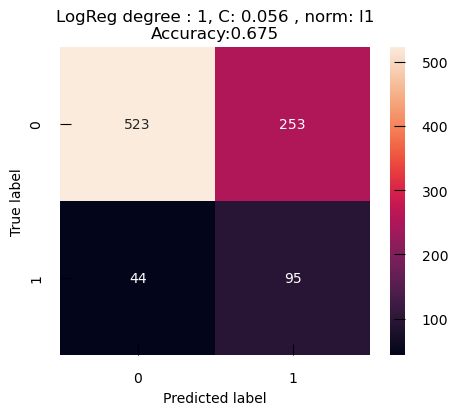

Let’s now predict the results on the test data:

y_cancer_test_pred = grid_cancer.predict(X_test_cancer)

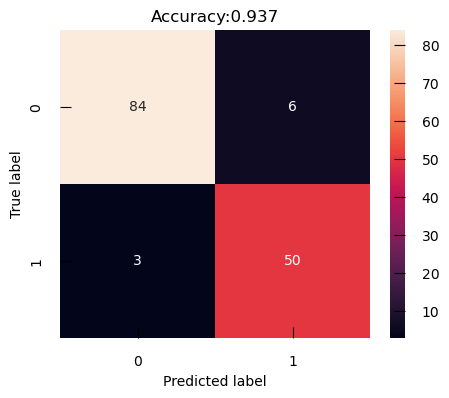

The Confusion Matrix is a table to visualize and evaluate the performance of the classification model. It’s a powerful tool for understanding how well our model is doing, where it’s going wrong, and what we can do to improve it. It shows the number of true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), and false negatives (FN) in our classification results:

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score, confusion_matrix

confusion_m_cancer = confusion_matrix(y_test_cancer, y_cancer_test_pred)

plt.figure(figsize=(5,4))

sns.heatmap(confusion_m_cancer, annot=True)

plt.title(f"Accuracy:{accuracy_score(y_test_cancer,y_cancer_test_pred):.3f}")

plt.ylabel("True label")

plt.xlabel("Predicted label")

With its default threshold of 0.5, this model tends to produce more False Positive, i.e. benign cancer seen as malignant, than False Negative, i.e. malignant cancer seen as benign. Depending on the particular of the problem we are trying to solve, that may be a desirable outcome.

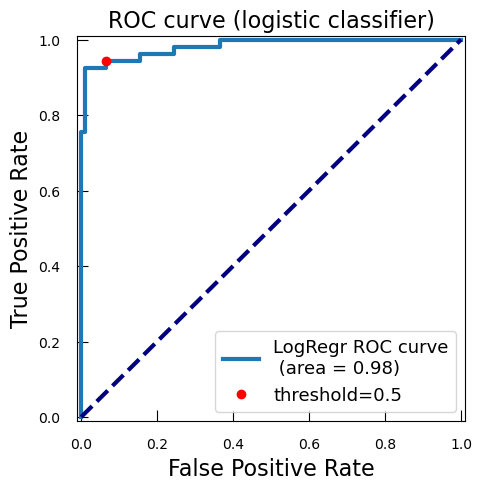

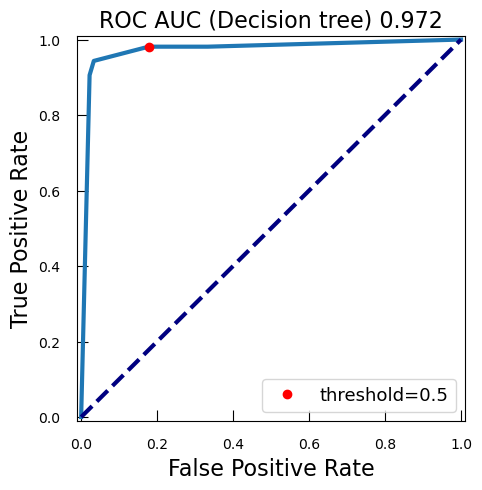

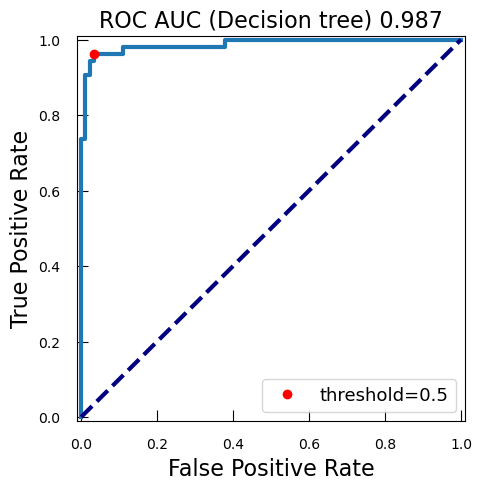

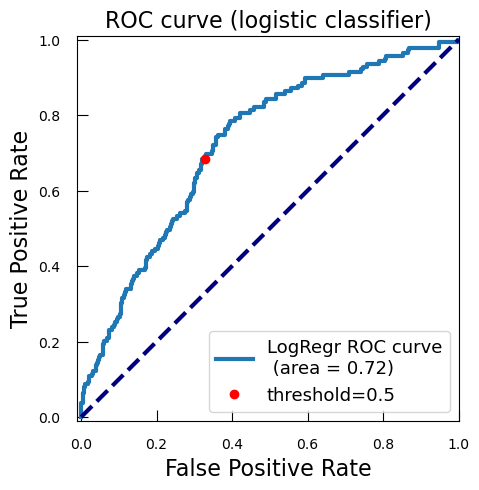

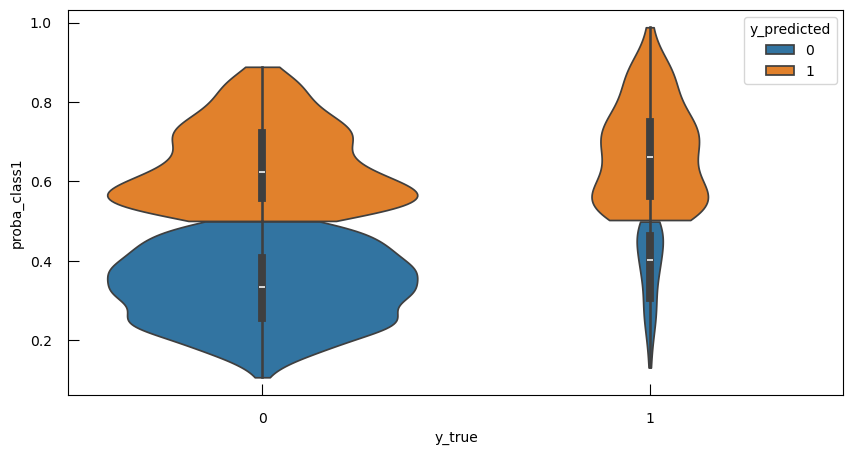

Whatever the case, it is always interesting to explore a bit more. We will plot how each possible threshold affect the True Positive Rate (TPR) and the False Positive Rate (FPR): the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (ROC curve).

-

With

predict_proba, we get the predicted probabilities for each class for the test data. We focus on the probability of being of the positive class (class 1), i.e. malignant, so we keep only the second columny_proba_lr_cancer = grid_cancer.predict_proba(X_test_cancer)[:, 1]In logistic regression, the model outputs a score known as the logit, which is the natural logarithm of the odds of the positive class. The logit is a linear combination of the input features and the model coefficients. To interpret these logits as probabilities, we need to convert them back to the probability scale using the sigmoid function, also known as the expit function.

from scipy.special import expit y_proba_lr_cancer = expit(y_score_lr_cancer)The logistic regression model calculates the logit for each input sample as a linear combination of the input features and the model coefficients.

Logit:

\( z= \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \beta_1 x_1 + \ldots + \beta_{n} x_{n} \)

with \( \beta_{0} \) is the intercept, \(\beta_1\), \(\beta_2\), \(\ldots\), \(\beta_{n}\) are the coefficients, and \(x_1\), \(x_2\), \(\ldots\), \(x_n\) are the input features.

To convert the logit \(z\) to a probability \(p\), we apply the expit function:

\( p=expit(z)= \frac{1}{1+e^{−z}}\)

This conversion ensures that the output is a valid probability, i.e., a value between 0 and 1.

-

We calculates now the ROC curve with TPR and FPR for each threshold of score

from sklearn.metrics import roc_curve fpr_lr_cancer, tpr_lr_cancer, threshold_cancer = roc_curve( y_test_cancer, y_proba_lr_cancer ) -

We find the point corresponding to a 0.5 theshold:

keep = np.argmin(np.abs(threshold_cancer - 0.5)) -

We compute the area under the ROC curve (AUC):

from sklearn.metrics import auc roc_auc_lr_cancer = auc(fpr_lr_cancer, tpr_lr_cancer)AUC is a widely used metric for evaluating the performance of classification models, particularly in the context of binary classification. The AUC is calculated as the area under the ROC curve. It ranges from 0 to 1. A model with no discrimination ability (random guessing) has an AUC of 0.5. A perfect model has an AUC of 1.

Why is AUC Important?

- Threshold-Independent: AUC provides a single scalar value that summarizes the performance of the classifier across all possible thresholds. This makes it a threshold-independent metric.

- Discrimination Ability: AUC measures the ability of the model to discriminate between positive and negative classes. A higher AUC indicates better model performance.

- Comparative Metric: AUC is useful for comparing the performance of different models or different configurations of the same model.

-

We plot the ROC, TPR, and FPR:

plt.figure() plt.xlim([-0.01, 1.01]) plt.ylim([-0.01, 1.01]) plt.plot( fpr_lr_cancer, tpr_lr_cancer, lw=3, label=f"LogRegr ROC curve\n (area = {roc_auc_lr_cancer:0.2f})" ) plt.plot(fpr_lr_cancer[keep], tpr_lr_cancer[keep], "ro", label="threshold=0.5") plt.xlabel("False Positive Rate", fontsize=16) plt.ylabel("True Positive Rate", fontsize=16) plt.title("ROC curve (logistic classifier)", fontsize=16) plt.legend(loc="lower right", fontsize=13) plt.plot([0, 1], [0, 1], color="navy", lw=3, linestyle="--") plt.show()

So with this ROC curve, we can see how the model would behave on different thresholds.

QuestionWe have marked the 0.5 threshold on the plot. Where would a higher threshold be on the curve?

A higher threshold means a lower False Positive Rate, so we move down and to the left in the curve.

For now, let’s put this aside briefly to explore a very common problem in classification: imbalance.

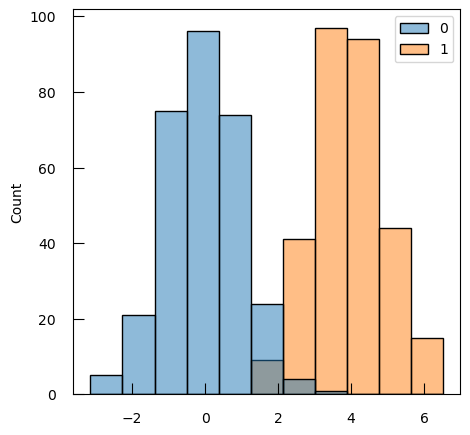

Imbalanced dataset

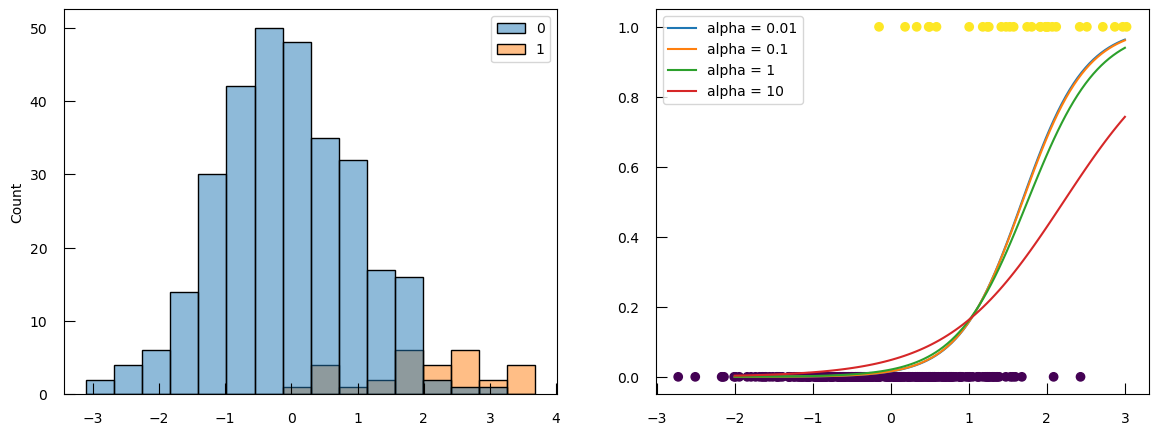

Let’s use the same small example as before, but now instead of 300 sample of each class, imagine we only have 30 samples of class 1:

X1 = np.concatenate([np.random.randn(300), np.random.randn(30)+2])

y = np.array([0]*300 + [1]*30)

# do not forget to scale the data

X1_norm = StandardScaler().fit_transform(X1.reshape(X1.shape[0], 1 ))

fig,ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(14,5))

sns.histplot(x=X1, hue=y, ax=ax[0])

ax[1].scatter(X1_norm, y, c=y)

for alpha in [0.01, 0.1, 1, 10]:

# this implementation does not take alpham but rather C = 1/alpha

C = 1/alpha

lr = LogisticRegression(penalty="l2", C=C)

lr.fit(X1_norm, y)

proba = lr.predict_proba(np.linspace(-2, 3, 100).reshape(-1, 1))

ax[1].plot(np.linspace(-2, 3, 100), proba[:,1], label=f"alpha = {alpha}")

ax[1].legend()

The point where the probability curves for different alpha converge is not 0.5 anymore. And the probability says fairly low even at the right end of the plot.

y_predicted = lr.predict(X1_norm)

print(f"Accuracy with a threshold of 0.5 : {accuracy_score(y,y_predicted):.2f}")

pd.crosstab(y, y_predicted)

Question

- What is the accuracy with a threshold of 0.5?

- Using this cross-tabulation, how many TP, TN, FP, FN are there?

- 0.92

The cross-tabulation is:

col_0 0 1 row_0 0 299 1 1 24 6 So:

- TP = 6

- TN = 299

- FP = 1

- FN = 24

Most sample of the class 1 samples are miss-classified (24/30), but we still get a very high accuracy. That is because, by contruction, both the logistic regression and accuracy score do not differentiate False Positive and False Negative.

And the problem gets worse the more imbalance there is.

from sklearn.metrics import recall_score

recall_list = [] # TP / (TP + FN)

acc_list = []

imbalance_list = np.linspace(0, 1, 50)

alpha = 1

for imbalance in imbalance_list:

n0 = 300

n1 = int(n0 * (1 - imbalance))

if n1 == 0:

n1 = 1

X1 = np.concatenate([np.random.randn(n0), np.random.randn(n1)+2])

y = np.array([0]*n0 + [1]*n1)

X1_norm = StandardScaler().fit_transform(X1.reshape(X1.shape[0], 1))

C = 1/alpha

lr = LogisticRegression(penalty = "l2", C = C)

lr.fit(X1_norm , y)

y_predicted = lr.predict(X1_norm)

recall_list.append(recall_score(y, y_predicted))

acc_list.append(accuracy_score(y, y_predicted))

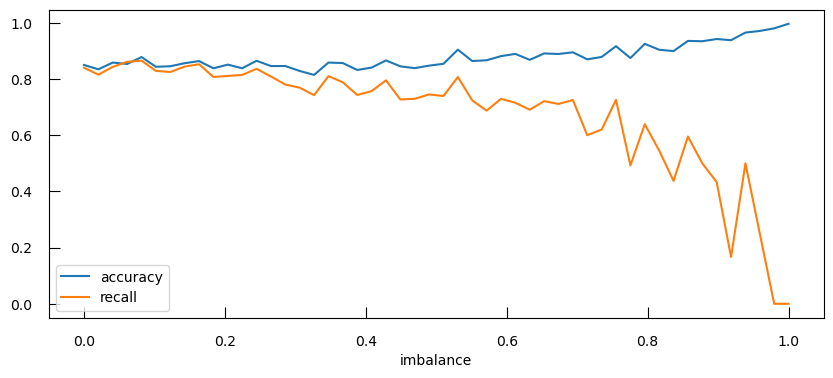

fig,ax=plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 4))

ax.plot(imbalance_list, acc_list, label="accuracy")

ax.plot(imbalance_list, recall_list, label="recall")

ax.set_xlabel("imbalance")

ax.legend()

Not only does the precision get worse, the accuracy actually gets higher as there is more imbalance!

This can lead to several issues:

- Model Bias: imbalance in the dataset skews the logistic regression toward predicting the majority class more frequently. This is because the model aims to minimize the overall error, and predicting the majority class more often results in fewer errors. As a result, the model may perform poorly on the minority class, leading to low recall and precision for that class.

- Metric Limitations: accuracy does not differenciate between False Positive and False Negative, making it blind to imbalance. Indeed, a model that predicts the majority class for all instances can achieve high accuracy but fail to identify the minority class.

To address these issues, the solutions will have to tackle both the model and the evaluation metric.

-

For the logistic regression - Re-weighting Samples: One effective approach is to re-weight the samples according to their class frequency during the model fitting process. This ensures that the minority class instances are given more importance, helping the model to learn better from the imbalanced data.

In

scikit-learn, this can be achieved using theclass_weightparameter in theLogisticRegressionclass. Settingclass_weight="balanced"automatically adjusts the weights inversely proportional to the class frequencies. -

For the metric, there exists several metrics which are sensitive to imbalance problems. Here we will introduce the balanced accuracy, a metric that accounts for class imbalance by calculating the average of the recall (true positive rate) for each class:

\[balanced\_accuracy = 0.5*( \frac{TP}{TP+FN} + \frac{TN}{TN+FP} )\]CommentOther possible metrics:

- average precision (AP) score

- F1 score, also known as balanced F-score or F-measure

Both linked to the precision/recall curve.

Let’s see the impact of re-weighting samples and using balanced accuracy:

from sklearn.metrics import balanced_accuracy_score

def check_imbalance_effect(imbalance_list, class_weight = None):

recall_list = []

balanced_acc_list = []

acc_list = []

for imbalance in imbalance_list:

n0 = 300

n1 = int(n0 * (1 - imbalance))

if n1 == 0:

n1 = 1

X1 = np.concatenate([np.random.randn(n0), np.random.randn(n1)+2])

y = np.array([0]*n0 + [1]*n1)

X1_norm = StandardScaler().fit_transform(X1.reshape(X1.shape[0], 1))

# LR

lr = LogisticRegression(penalty="l2", C=1, class_weight=class_weight)

lr.fit(X1_norm, y)

y_predicted = lr.predict(X1_norm)

recall_list.append(recall_score(y , y_predicted))

acc_list.append(accuracy_score(y, y_predicted))

balanced_acc_list.append(balanced_accuracy_score(y, y_predicted))

return recall_list, acc_list, balanced_acc_list

imbalance_list = np.linspace(0, 1, 50)

recall_list, acc_list, balanced_acc_list = check_imbalance_effect(

imbalance_list,

class_weight=None,

)

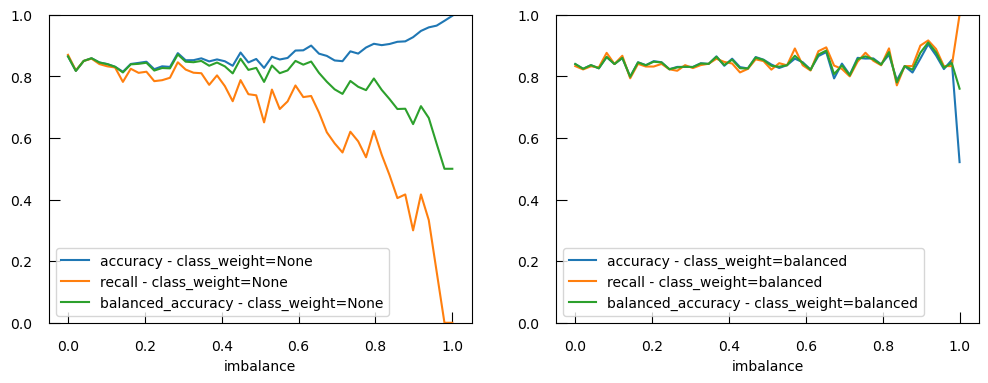

fig,ax=plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(12, 4))

ax[0].plot(imbalance_list, acc_list, label="accuracy - class_weight=None")

ax[0].plot(imbalance_list, recall_list, label="recall - class_weight=None")

ax[0].plot(

imbalance_list,

balanced_acc_list,

label="balanced_accuracy - class_weight=None",

)

ax[0].set_xlabel("imbalance")

ax[0].set_ylim(0, 1)

ax[0].legend()

## now, with class weight

recall_list, acc_list, balanced_acc_list = check_imbalance_effect(

imbalance_list,

class_weight="balanced"

)

ax[1].plot(imbalance_list, acc_list, label="accuracy - class_weight=balanced" )

ax[1].plot(imbalance_list, recall_list, label="recall - class_weight=balanced" )

ax[1].plot(

imbalance_list,

balanced_acc_list,

label="balanced_accuracy - class_weight=balanced",

)

ax[1].set_xlabel("imbalance")

ax[1].set_ylim(0, 1)

ax[1].legend()

The balanced accuracy is able to detect an imbalance problem and setting class_weight="balanced" in our logistic regression fixes the imbalance at the level of the model.

Comment: A few VERY IMPORTANT words on leakageThe most important part in all of the machine learning jobs that we have been presenting above, is that the data set on which you train and the data set on which you evaluate your model should be clearly separated (either the validation set when you do hyperparameter tunning, or test set for the final evaluation).

No information directly coming from your test or your validation should pollute your train set. If it does you loose your ablity to have a meaningful evaluation power.

In general data leakage relates to every bits of information that you should not have access to in a real case scenario, being present in your training set.

Among those examples of data leakage you could count :

- using performance on the test set to decide which algorithm/hyperparameter to use

- doing imputation or scaling before the train/test split

- inclusion of future data points in a time dependent or event dependent model.

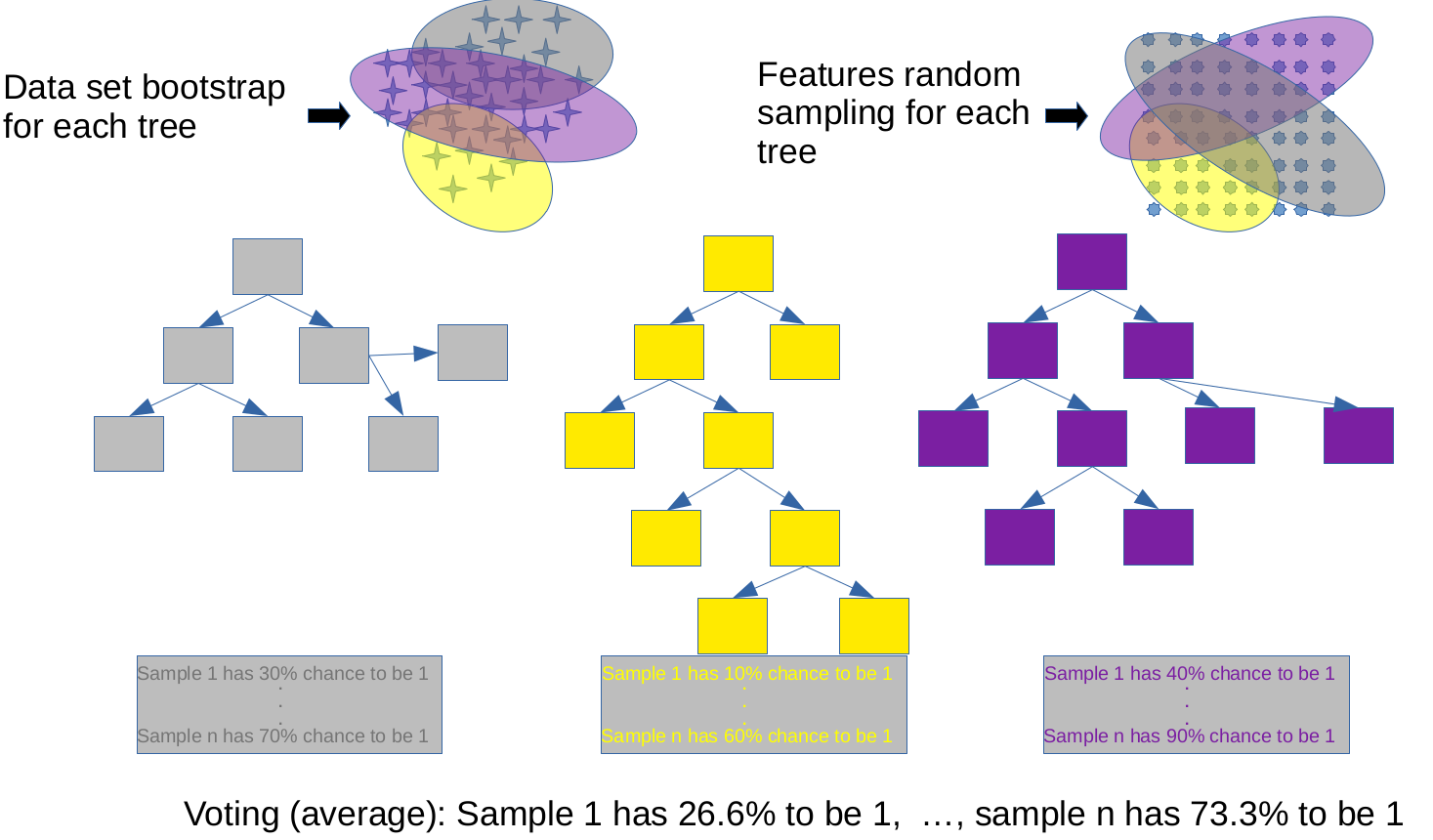

Decision tree modeling

Having explored the intricacies of logistic regression, including techniques to handle class imbalance and evaluate model performance using metrics like balanced accuracy, we now turn our attention to another powerful and versatile machine learning algorithm: decision trees. While logistic regression is a linear model that is well-suited for binary classification problems, decision trees offer a different approach, capable of capturing complex, non-linear relationships in the data: a (new?) loss function and new ways to do regularization. Decision trees are particularly useful for their interpretability and ability to handle both classification and regression tasks, making them a valuable tool in the machine learning toolkit.

By understanding decision trees and their regularization techniques, we will gain insights into how to build models that can capture intricate patterns in the data while avoiding overfitting. Let’s dive into the world of decision tree modeling and discover how this algorithm can be applied to a wide range of predictive tasks.

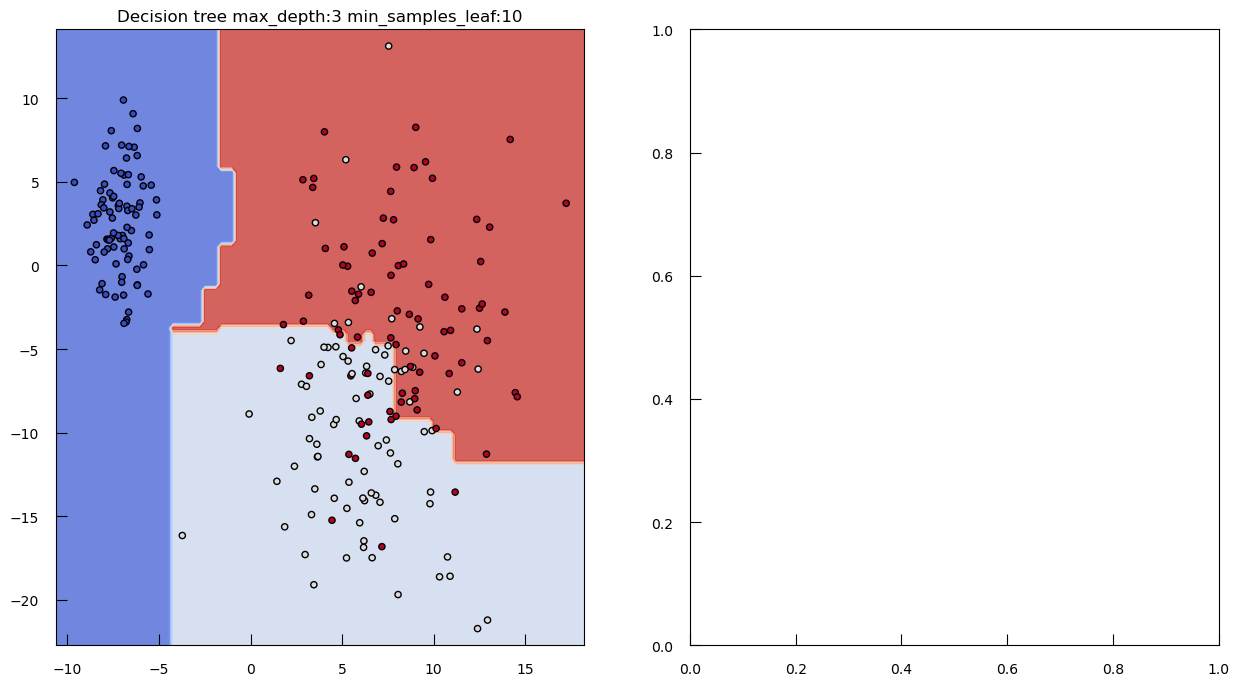

Simple decision tree for classification

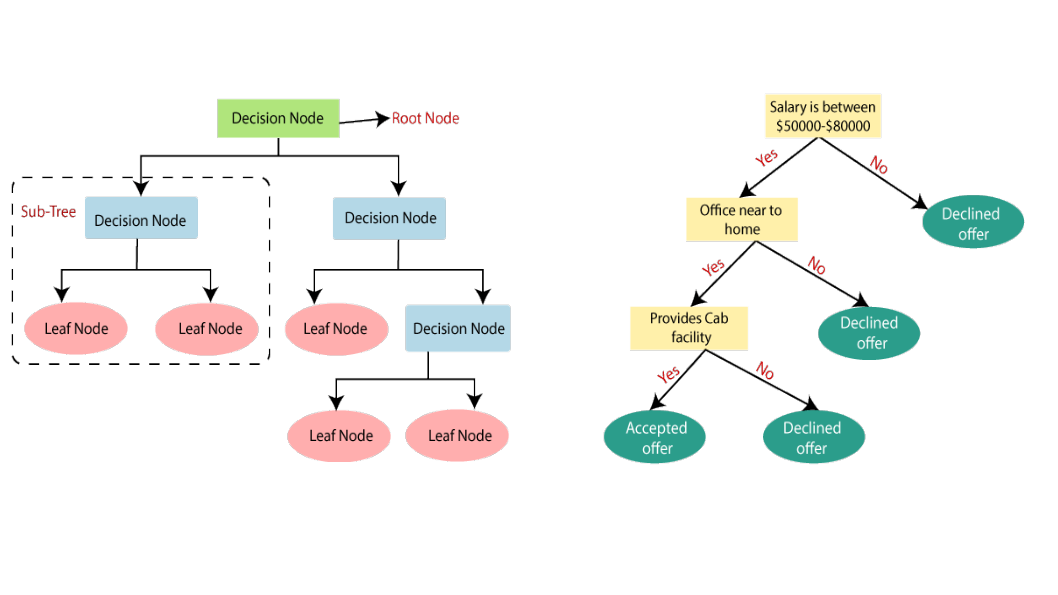

A decision tree is a powerful and intuitive machine learning algorithm that breaks down complex problems into a hierarchical sequence of simpler questions. This process subdivides the data into increasingly specific subgroups, each defined by the answers to these questions. Here’s how it works:

- Hierarchical Structure:

- A decision tree starts with a single node, known as the root node, which represents the entire dataset.

- From the root, the tree branches out into a series of internal nodes, each representing a question or decision based on the features of the data.

- Binary Splits:

- At each internal node, the decision tree asks a yes-or-no question about a feature. The answer to this question determines which branch to follow next.

- This binary split divides the data into two subgroups: one where the condition is met (yes) and another where it is not (no).

- Recursive Partitioning:

- The process of asking questions and splitting the data continues recursively for each subgroup. Each new question further subdivides the data into more specific subgroups.

- This recursive partitioning continues until a stopping criterion is met, such as a maximum tree depth, a minimum number of samples per node, or pure leaf nodes where all samples belong to the same class.

- Leaf Nodes:

- The final nodes in the tree, known as leaf nodes, represent the outcomes or predictions for the subgroups of data.

- In classification tasks, leaf nodes assign a class label to the samples in that subgroup. In regression tasks, leaf nodes provide a predicted value.

A huge number of trees can actually be built just by considering the different orders of questions asked. How does the algorithm deals with this? Quite simply actually: it tests all the features and chooses the most discriminative (with respect to your target variable), i.e. the feature where a yes or no question divides the data into 2 subsets which minimizes an impurity measure.

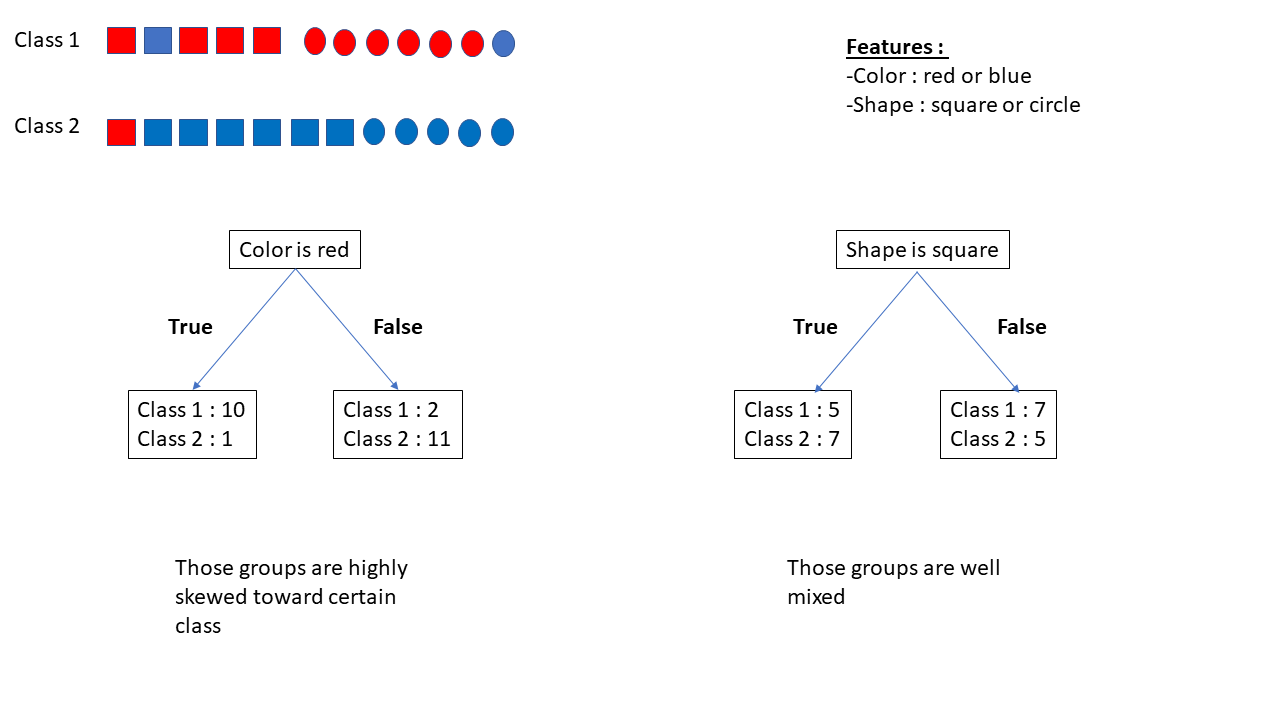

Let’s imagine we have a dataset with feature color (red or blue), feature shape (square or circle), and 2 target classes (1 and 2):

If we ask whether the feature “color is red,” we get the following subgroups:

- 10 instances of Class 1 and 1 instance of Class 2 (

if "feature color is red" == True) - 2 instances of Class 1 and 11 instances of Class 2 (

if "feature color is red" == False)

Asking whether the “feature shape is square” gives us:

- 5 instances of Class 1 and 7 instances of Class 2 (if True)

- 7 instances of Class 1 and 5 instances of Class 2 (if False)

We will prefer asking “feature color is red?” over “feature shape is square?” because “feature color is red?” is more discriminative.

For categorical variables, the questions test for a specific category. For numerical variables, the questions use a threshold as a yes/no question. The threshold is chosen to minimize impurity. The best threshold for a variable is used to estimate its discriminativeness.

Of course, we will need to compute this threshold at each step of our tree since, at each step, we are considering different subsets of the data.

The impurity is related to how much our feature splitting is still having mixed classes. Impurity provides a score that indicates the purity of the split. Common measures of impurity include Shannon entropy and the Gini coefficient.

-

Shannon Entropy: \( \text{Entropy} = - \sum_{j} p_j \log_2(p_j) \)

This measure is linked to information theory, where the information of an event occurring is the \( \log_2 \) of the event’s probability of occurring. For purity, 0 is the best possible score, and higher values are worse.

-

Gini Coefficient: \( \text{Gini} = 1 - \sum_{j} p_j^2 \)

The idea is to measure the probability that a dummy classifier mislabels your data. 0 is best, and higher values are worse.

Toy dataset

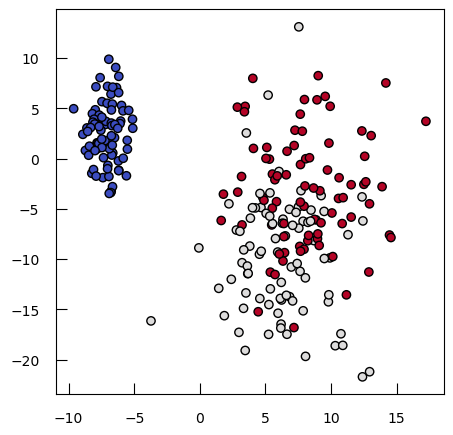

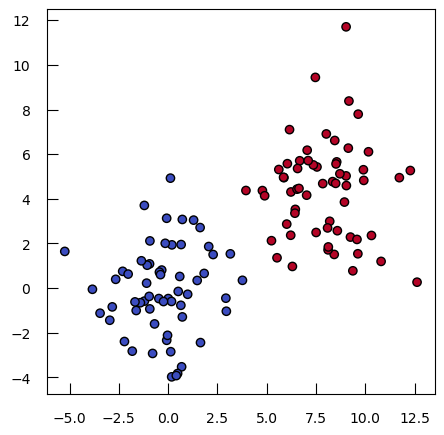

To see how both work in practice, let’s generate some toy data: a synthetic dataset with 250 samples distributed among three clusters. Each cluster has a specified center and standard deviation, which determine the location and spread of the data points.

from sklearn.datasets import make_blobs

blob_centers = np.array([[-7, 2.5], [6, -10], [8, -3]])

blob_stds = [[1, 3], [3, 6], [3, 6]]

X_3, y_3 = make_blobs(

n_samples=250,

centers=blob_centers,

cluster_std=blob_stds,

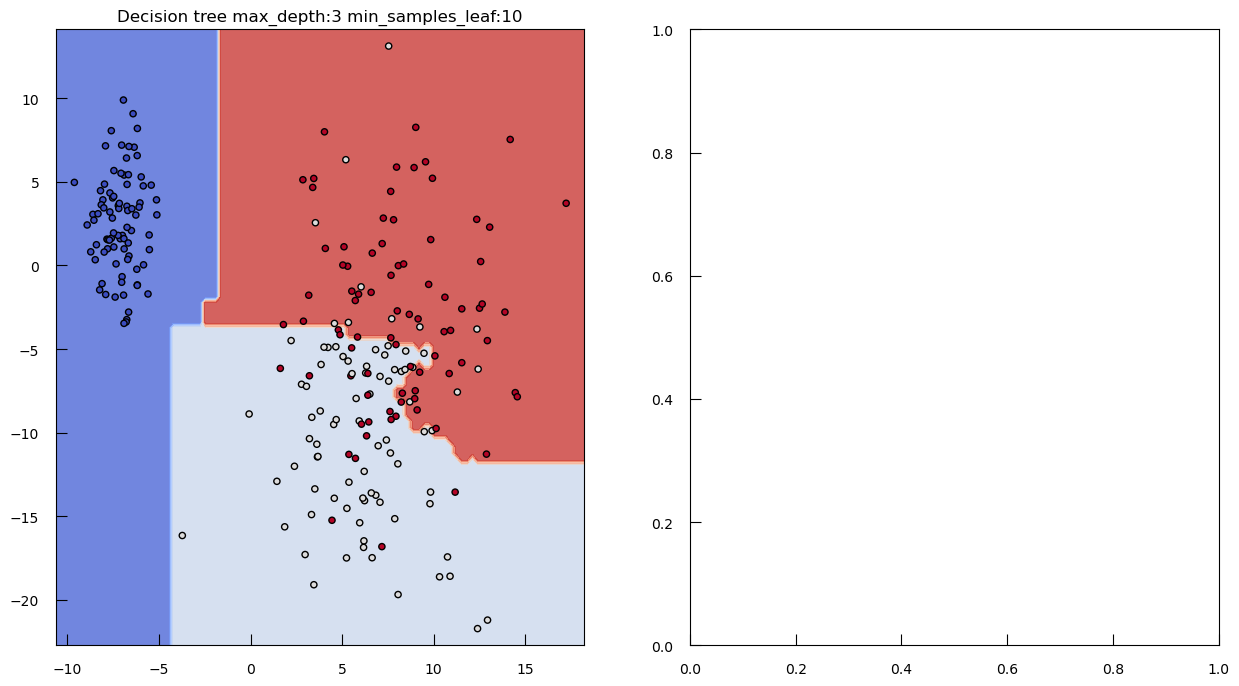

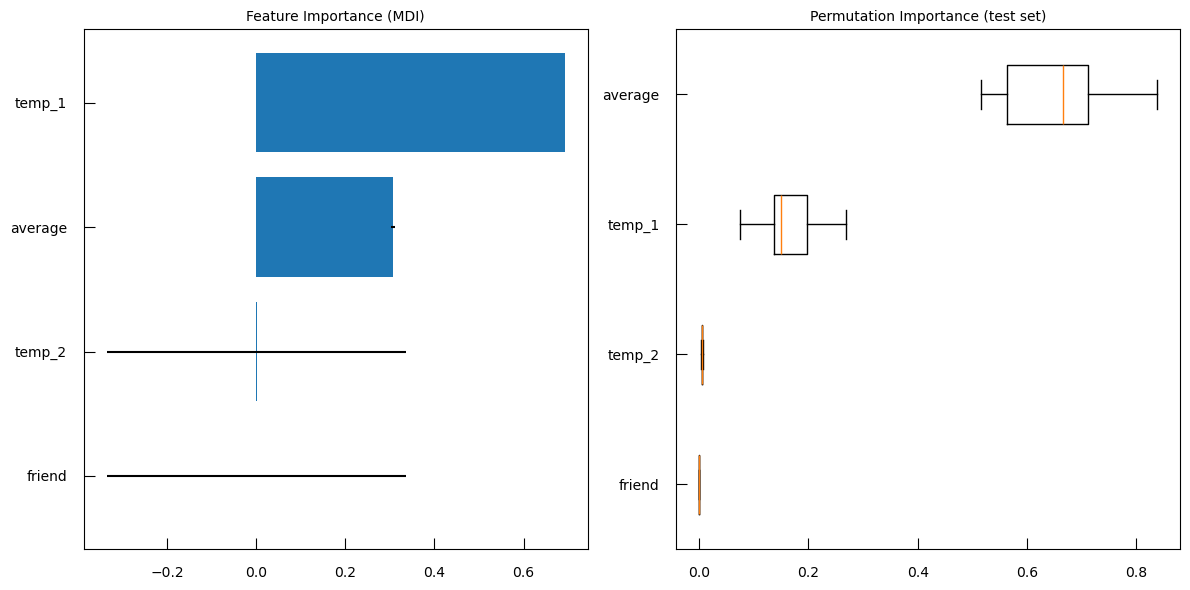

random_state=42