Python - Multiprocessing

| Author(s) |

|

| Editor(s) |

|

| Reviewers |

|

OverviewQuestions:

Objectives:

How can I parallelize code to make it run faster

What code is, or is not, a prime target for parallelisation

Requirements:

Understanding how to paralellise code to make it run faster.

Identifying how to decompose code into a parallel unit.

Time estimation: 30 minutesLevel: Advanced AdvancedSupporting Materials:Published: Oct 19, 2022Last modification: Nov 16, 2023License: Tutorial Content is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The GTN Framework is licensed under MITpurl PURL: https://gxy.io/GTN:T00095version Revision: 4

Best viewed in a Jupyter NotebookThis tutorial is best viewed in a Jupyter notebook! You can load this notebook one of the following ways

Run on the GTN with JupyterLite (in-browser computations)

Launching the notebook in Jupyter in Galaxy

- Instructions to Launch JupyterLab

- Open a Terminal in JupyterLab with File -> New -> Terminal

- Run

wget https://training.galaxyproject.org/training-material/topics/data-science/tutorials/python-multiprocessing/data-science-python-multiprocessing.ipynb- Select the notebook that appears in the list of files on the left.

Downloading the notebook

- Right click one of these links: Jupyter Notebook (With Solutions), Jupyter Notebook (Without Solutions)

- Save Link As..

This tutorial will introduce you to the basics of Threads and Processes in Python and how you can use them to parallelise your code.

AgendaIn this tutorial, we will cover:

Threads vs Processes

For many languages, threads can be extremely efficient, as they are rather light weight and don’t require many resources to create new threads. “Threads are cheap”. However Python has a major limitation with the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL). Only one thread can be executing at once, whether it’s the main thread, or one of the others you’ve spawned. So we look to alternative concurrency mechanisms like processes for sharing the load across multiple CPU cores.

For threads, if you are doing “lightweight” work like fetching data from the web where a lot of time is spent waiting for the server to respond, but very little computational work within Python is required, then threads are a great fit!

However if you are doing computationally intensive work (imagine calculating prime numbers or similar complex tasks) then each thread will be contending for CPU time. Python is a single processes and can only have one thread running at a time due to the GIL. So it will switch between multiple threads and try and make progress on each, but it cannot execute them truly simultaneously. Here we need to switch to processes.

Processes are relatively heavier weight as they essentially start a new python process, before executing the individual function. This is part of the reason for a “Pool”, to amortise the expensive cost of setting up processes, before allowing them to do a lot of work quickly. Here each process can be using it’s own CPU core fully, and thus make more sense for computationally expensive tasks.

Let’s dive straight into an example: here we’re using the multiprocessing library which uses processes and is relatively simple to understand:

from multiprocessing import Pool

Importantly we should define a pure function, i.e. a function that only works on the inputs available to it, and doesn’t use or affect global state (i.e. without side effects). (printing is ok.)

def f(x):

return x * x

We spawn a process Pool, with 5 processes And then use the convenient map

function to send inputs multiply to the specified function f

with Pool(5) as p:

print(p.map(f, range(10)))

This will create 5 new python processes, and they will begin to consume tasks from the queue as quickly as they can. As soon as a process has finished handling one task, it will begin work on the next task.

Pools & Paralellism

Let’s do another example, the classic “print time”, to see how the threads are actually executing across 4 processes.

import time

def g(x):

print(time.time())

time.sleep(1)

with Pool(4) as p:

print(p.map(g, range(12)))

QuestionWhat did you see here?

Was it clear and easy to read?

It prints four timestamps immediately, all around the same time. Then one second later it prints 4 more, and one second later, a final four. Our Pool of 4 processes processes the function the maximal amount of times possible concurrently. Once each of those functions returns, then it can move on to processing the next tasks. This is precisely the situation of e.g. 4 queues at the grocery; as soon as one customer is processed, they immediately begin on the next, until no more remain.

You might also see a situation where the numbers are interleaved in a completely unreadable way. Here they write immediately, but there is no synchronisation or limiting on who can write at one time, and the result is a mess of interleaved print statements.

When to parallelise

Some guidelines:

- When you can isolate a pure function

- That do not require shared state, nor ordering

- That do not modify global state (pure!)

- That take a significant amount of time, relative to the time it takes to rewrite your code to support parallelising.

Some common examples of this are slow tasks like requesting data from multiple websites, e.g. using the requests library. Or doing some computationally expensive calculation. The last point however is especially important, as it is not always trivial to rearchitect your code to handle being spread across multiple threads or processes.

Let’s parallelize this program which fetches some metadata from multiple Galaxy servers:

import requests

import time

servers = [

"https://usegalaxy.org",

"https://usegalaxy.org.au",

"https://usegalaxy.eu",

"https://usegalaxy.fr",

"https://usegalaxy.be",

]

data = {}

start = time.time()

for url in servers:

print(url)

try:

response = requests.get(url + "/api/version", timeout=2).json()

data[url] = response['version_major']

except requests.exceptions.ConnectTimeout:

data[url] = None

except requests.exceptions.ReadTimeout:

data[url] = None

# How long did it take to execute

print(time.time() - start)

for k, v in data.items():

print(k, v)

If we look at this, we can see one hot spot in the code, where it’s quite slow, requesting data from a remote server. If we want to speed this up we’ll need to isolate it into a pure function. Here we can see a possibility for a function that requests the data, with the input of the server url, and output of the version.

def fetch_version(server_url):

try:

response = requests.get(server_url + "/api/version", timeout=2).json()

return response['version_major']

except requests.exceptions.ConnectTimeout:

return None

except requests.exceptions.ReadTimeout:

return None

This now lacks side effects (like modifying the data object), and can be used in a map statement.

start = time.time()

with Pool(4) as p:

versions = p.map(fetch_version, servers)

data = dict(zip(servers, versions))

print(time.time() - start)

for k, v in data.items():

print(k, v)

Same result, and now this is a lot more efficient!

Sizing your Pool

This depends largely on profilling your code or knowing the performance characteristics of it. In the above example, there is very little computation work executed as part of this function, it’s essentially all network I/O, no CPU or memory usage.

As such, we can probably set our pool size to be very large, a multiple of our systems’ processor count. It will spawn many processes that do very little.

If however this were a more complicated task (e.g. calculating a large number, machine learning, etc.), then we might wish to set our pool size to the number of CPUs - 1, as each process will potentially consume it’s CPU allocation completely, and we wish to have some left over for the managing program and any other work going on, on the system.

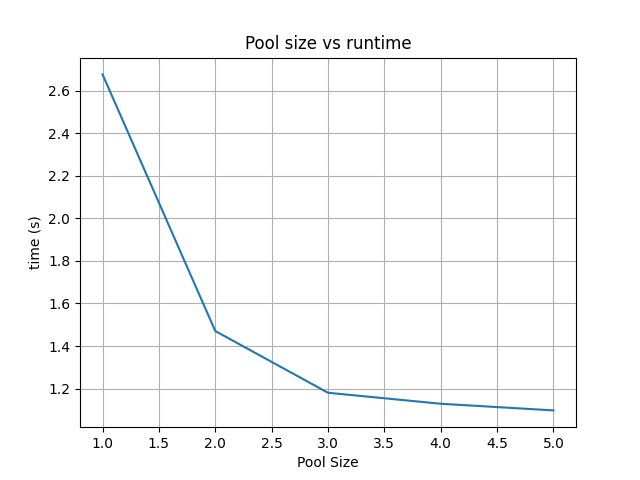

QuestionTry changing the pool size and see what effect it has on runtime. Start from a value of 1, and go up to 5, the number of servers in our list.

Given the small sample size (5 servers), and the variability of response times (in local testing between 3-8 seconds for the single-pool version), you can see varying results but generally it should decrease as the pool size increases. However, sometimes you will see the Pool=5 version take the same or longer than Pool=4.

Especially in the case that 1 server (or 1 request one time) dominates the request time, this can “hide” the improvements as the others complete quickly on the remaining N-1 processes.

results = []

for i in range(1, 6):

start = time.time()

with Pool(i) as p:

versions = p.map(fetch_version, servers)

data = dict(zip(servers, versions))

duration = time.time() - start

results.append(duration)

# Plot it

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(range(1, 6), results)

ax.set(ylabel='time (s)', xlabel='Pool Size', title='Pool size vs runtime')

ax.grid()

# Uncomment if your notebook cannot display images inline.

# fig.savefig("pool-vs-runtime.png")

plt.show()

You might see a result similar to the following:

Threads

Let’s convert our previous example from processes to threads, as processes aren’t strictly necessary for such a light weight use case as fetching data from the internet where you’re blocking on network rather than CPU resources.

import multiprocessing.pool

import requests

import time

data = {}

start = time.time()

pool = multiprocessing.pool.ThreadPool(processes=4)

results = pool.map(fetch_version, servers, chunksize=1)

data = {k: v for (k, v) in zip(servers, results)}

pool.close()

print(time.time() - start)

for k, v in data.items():

print(k, v)

This is a bit more complicated to write, but again, if you’re not blocking on CPU resources, then this is potentially approximately as effecient as thread pools.

QuestionWhat result did you get? Was it slower, faster, or about the same as processes?